What are your pronouns and why does it matter?

Descriptif

It is almost a platitude today to say that pronouns are political. Recently, however, they seem to have become more political than ever. Putting pronouns on a social network bio, in an email signature, on badges at conferences, or disclosing them during a pronoun round, i.e., introducing oneself with the formula “Hi my name is X and my pronouns are she/her, he/him, they/them…” is more than simply stating a fact, it is an intrinsically political act. These practices reveal much more than someone’s gender, they also indicate their stance on gender politics, and potentially much wider political issues.

However, as these pronoun-sharing practices have gained momentum and become more popular, they have also provoked backlash from certain quarters: in March 2023 Ron DeSantis, governor of Florida, signed a new state law against what he dubbed “the pronoun olympics”. It is now illegal in K12 educational institutions in Florida to refer to someone, or to ask to be referred to, with a pronoun that does not correspond to the sex assigned at birth, demonstrating just how politically charged pronouns have become.

This two-day hybrid interdisciplinary conference will focus on these recent pronoun-sharing practices, covering all forms of disclosing one’s pronouns including name badges, the pronoun round, putting pronouns in an email signature, Zoom profile, etc. What theories, methodologies and approaches can be mobilised to explain these new phenomena, as well as the backlash against them? What is the genealogy of these practices: how do they fit in with, or diverge from previous debates about pronouns?

Some argue (Cameron, 2016; Baron, 2020) that debates over pronouns in the 1960s and 70s focused on reducing the relevance of gender and imagining a world without gender. However, today gender is envisaged by many as a vital part of one’s identity. If second wave feminists conceptualised gender as a system of oppression, could asking, expecting or even obliging (Thomas-Hébert, 2022) people to disclose their pronouns be considered “just another way queer people are being pushed to perform their queerness” (De Freitas, 2021), a compulsory “pronominal coming out”? Even if the objective of these practices is to question the stability, universality, and binarity of gender (Thomas-Hébert, 2022), is there nonetheless an inherent paradox in wanting to question gender binaries, wanting to avoid pigeonholing people, and yet at the same time asking them to put a label on themselves? Have these practices unwittingly amplified gender binaries, simply creating a new gender binary of transgender/cisgender, rather than challenging the binary system per se (Manion, 2018)? What light can feminist and/or Queer theory shed on these issues?

The practice of disclosing one’s pronouns originated in trans communities as a way to inform others about how to refer to them appropriately, but quickly spread to the mainstream. If the risk of being misgendered is much less present for cis people, why do they do it? Do these pronoun-sharing practices mean different things for different people?

From a sociolinguistics perspective, who is using these new practices and why? Thomas-Hébert (2022) found that cis women declared their pronouns more often that cis men and Tucker and Jones (2023) found that the most widely used pronouns on Twitter were she/her. What does this indicate? That cis women are more likely to be allies than cis men? That more trans women disclose their pronouns than trans men? How do we explain these differences?

Alternatively, these practices are perhaps not to be associated with categories of people (trans, cis, non-binary, gender non-conforming, etc.), so much as with the stances that they index (Eckert, 2008). Are they a way for cis people to show allyship, a way of indicating their stance and alignment (Du Bois, 2007; Kiesling, 2022a) on trans issues, or even a way of signalling wider political allegiances? If so, what are these stances and how have these new pronoun-sharing practices changed the indexical value of pronouns over recent years? Stating one’s pronouns seems to be increasingly tied to, not only gender issues, but a liberal/left-wing ideological position.

What does it mean when the practice is taken up by high profile politicians like Elizabeth Warren (Democrat Senator for Massachusetts) and Kamala Harris (Democrat Vice President of the USA) (King and Crowley 2023)? What stance is being taken in these cases? Is this real allyship or simply “virtue-signalling”, a performance of transgender inclusion that does little to advance transgender rights (Manion, 2018)?

Equally, how far can these pronoun-sharing practices be considered a form of “gender-washing” that companies and universities exploit in order to appear ethically irreproachable? In this context, do these new pronoun-sharing practices risk losing their political potential and simply becoming a conformist ritual of political correctness (Jones, 2022)? To what extent does pronoun sharing fit into the “political correctness” debate, if at all?

From a pragmatics perspective, what seems specific to these pronoun-sharing practices is the detour taken via the 3rd person, which is not used in the I-you dyad. These practices thus seem to be a social ritual as well as an exchange of information, fulfilling a socio-pragmatic function, or as Cameron (2016) argues, “a symbolic affirmation of the parties’ intention to conduct their subsequent dealings in good faith and with mutual respect.” How then, do current practices fit into previous research on pronouns? Is disclosing one’s pronouns (for a cis person) a politeness strategy (Conrod 2020; Brown and Levinson 1987), an act of solidarity/allyship, part of an ethics of care towards non-binary, gender non-conforming and trans people (Zimman, 2017; Conrod, 2022)?

This interdisciplinary conference welcomes proposals from a variety of disciplines including (but not restricted to) sociolinguistics, pragmatics, Critical Discourse Analysis, philosophy, cultural, civilisation or literary studies that shed light on how these new pronoun-sharing practices matter. Communications can exploit various data (ethnographic data, interviews, surveys, online corpora, press articles, autobiographies, novels, TV series, films…) from any critical perspective. Comparative linguistics approaches are welcome, as long as the focus is on English.

The conference aims to answer some of (but not exclusively) the following questions:

Who employs these new pronoun-sharing practices and why?

What do these practices index about a speaker? How does this practice relate to other political stances?

How have these new practices changed the indexical value of pronouns over recent years?

Do people choose different pronouns depending on the context (e.g., professional email signature, bio on dating sites, pronoun rounds…)? If so, why?

Apart from he/him, she/her and they/them, what other pronouns are used and why?

What are people’s attitudes to these new practices? How are they perceived?

If these new practices are the heir to past struggles for gender-neutral pronouns, to what extent are they the continuation of these struggles? In what ways is the debate about pronouns today different from that of the 1960s and 70s? How does the use of non-binary singular they impact the use and perception of singular they as a generic gender-neutral pronoun (“somebody called but they didn’t leave a message”)?

How can we explain the backlash against these practices? What role do these practices play in the current climate of the culture wars and moral panic about gender?

To what extent do these practices open up a positive space for those questioning gender norms? Is the invitation to become pronominally visible, and therefore to make public what might be private, a source of liberation or alternatively a source of potential anxiety? Does it generate opportunities for gender fluidity or simply reify gender divisions and therefore gender hierarchies?

How does this phenomenon play out in different languages compared to English, or in different varieties of English?

What is the future of this new phenomenon? Will it become widespread, partly also because it helps recipients of an email to identify the gender of someone whose first name might not be marked for gender?

Vidéos

“Epistemology and sharing one’s pronouns: First, second, or third-person knowledge?”, Alexandra Gil…

In this paper, I consider sharing one’s pronouns as an act that asserts self-knowledge and positions oneself in relation to an addressee and a shared social landscape: see me this way, interact with

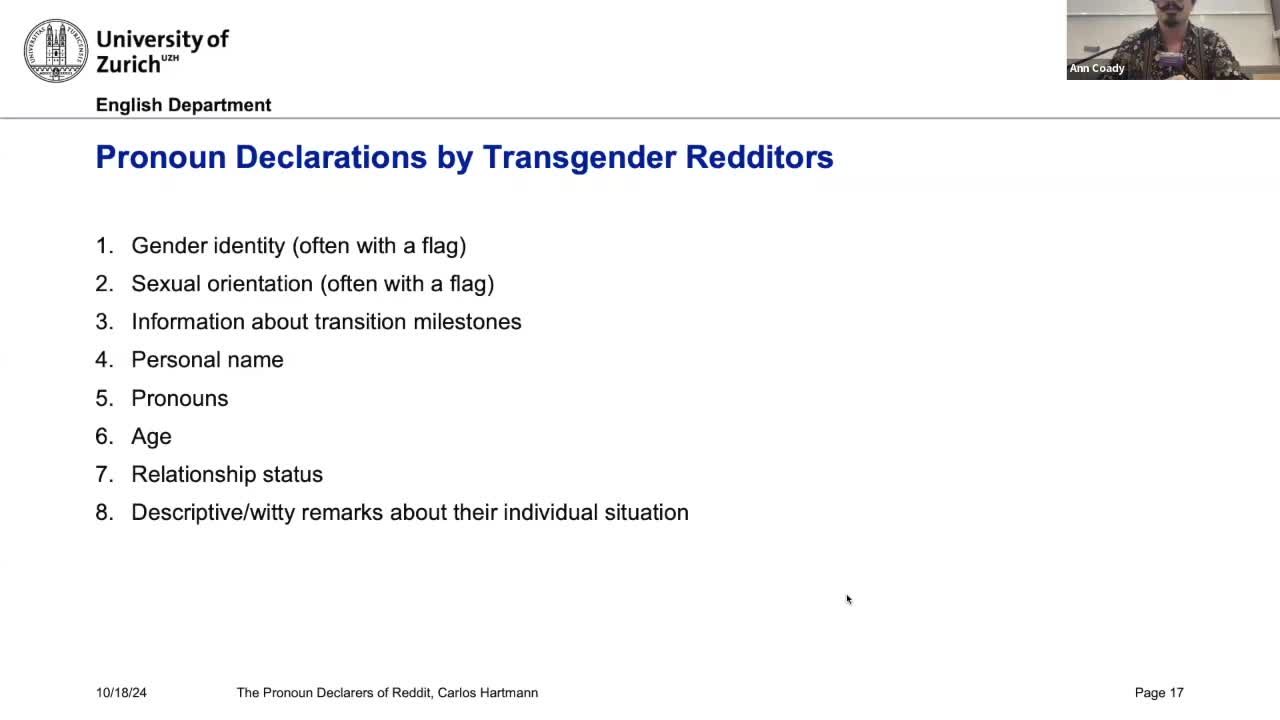

“A sociolinguistic case study on the Pronoun Declarers of Reddit”, Carlos Hartmann, Universität Zür…

For this study, I extracted and analyzed Reddit comments featuring pronoun declarations within their user flairs, the optional descriptors displayed alongside usernames. The goal was to identify a

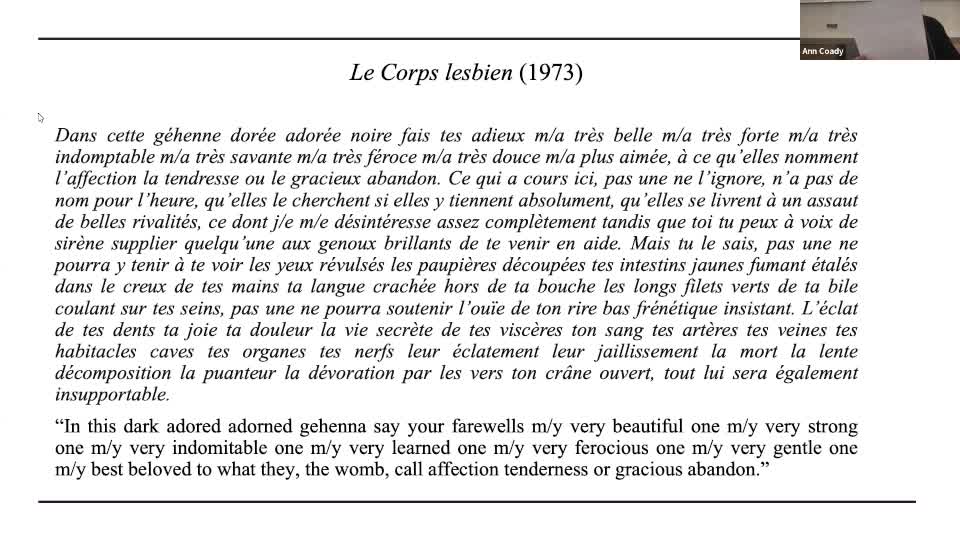

“Pronouns, past struggles, new practices: political continuity or radical change?”, Claudine Raynau…

I would like to compare two second wave French feminists’ thought and LGBTQIA+ theorizing and practice regarding pronouns and ponder their possible interactions. My focus will be the work of Luce

"Pronouns, positionality, and power: Institutionalized transphobia, intersectionality and trans-aff…

This talk explores the complex role of pronouns in the negotiation of (socio)linguistic justice, leading to the argument that the success of trans-affirming language depends on a broader

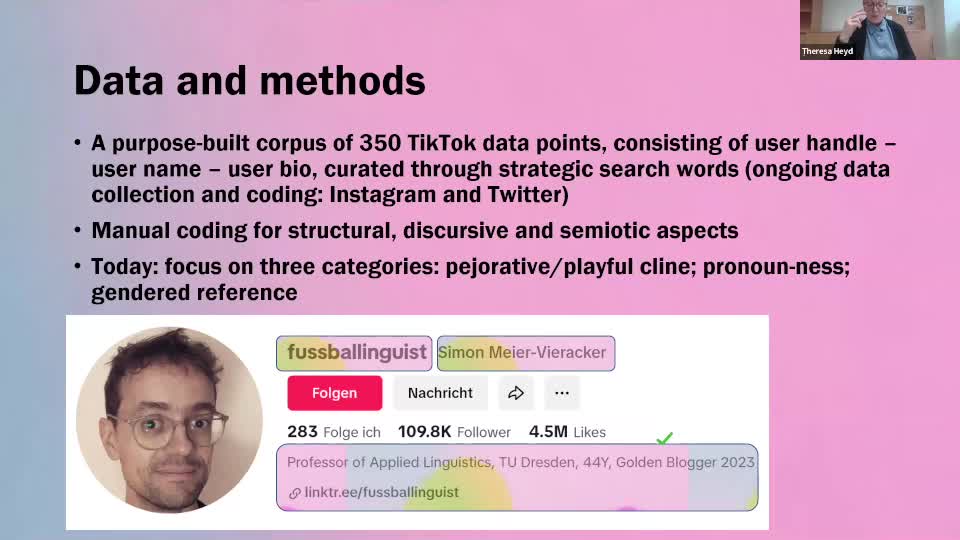

“Mock pronouns”, Theresa Heyd, Universität Heidelberg, Germany

This paper gives an account of mock pronouns as a (predominantly digital) discursive practice. The rise of pronouns and pronominal discourse as a gender-inclusive practice has been accompanied by

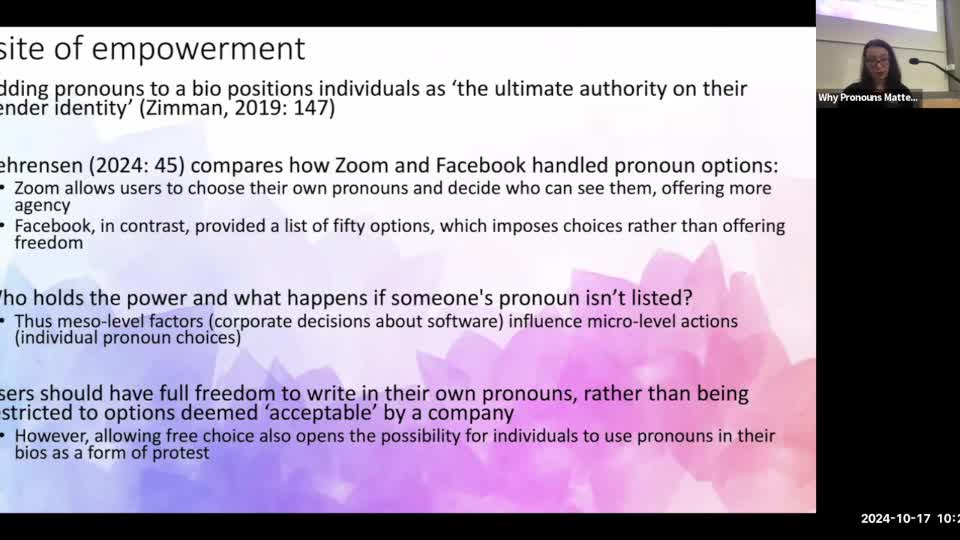

“Pronouns in bio: A site of empowerment, validation, struggle, performance, distraction, and corpor…

Pronouns in bio: A site of empowerment, validation, struggle, performance, distraction, and corporate rainbow washing?

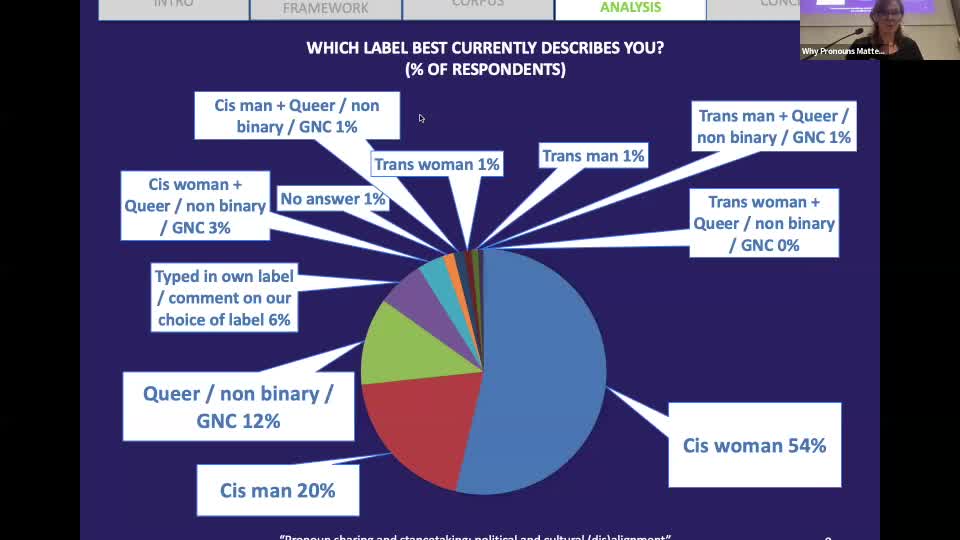

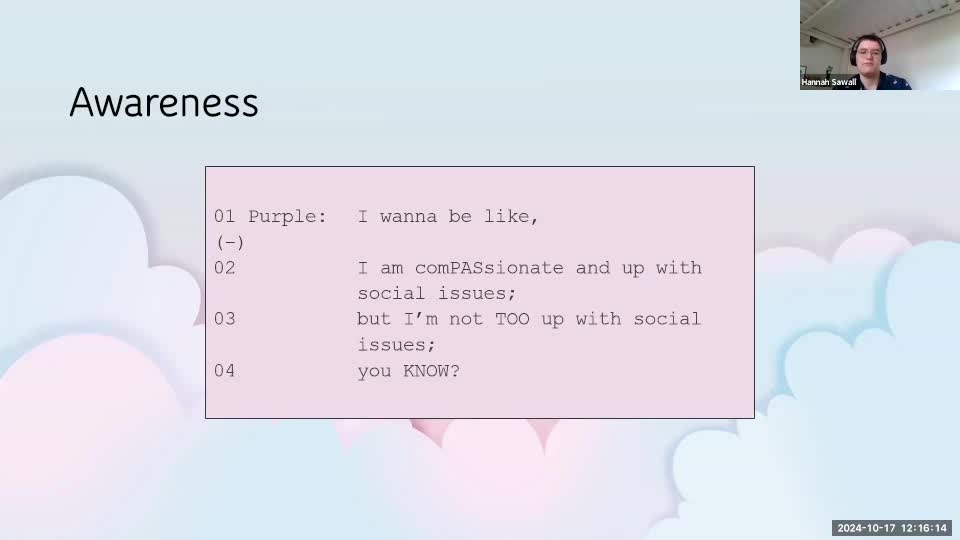

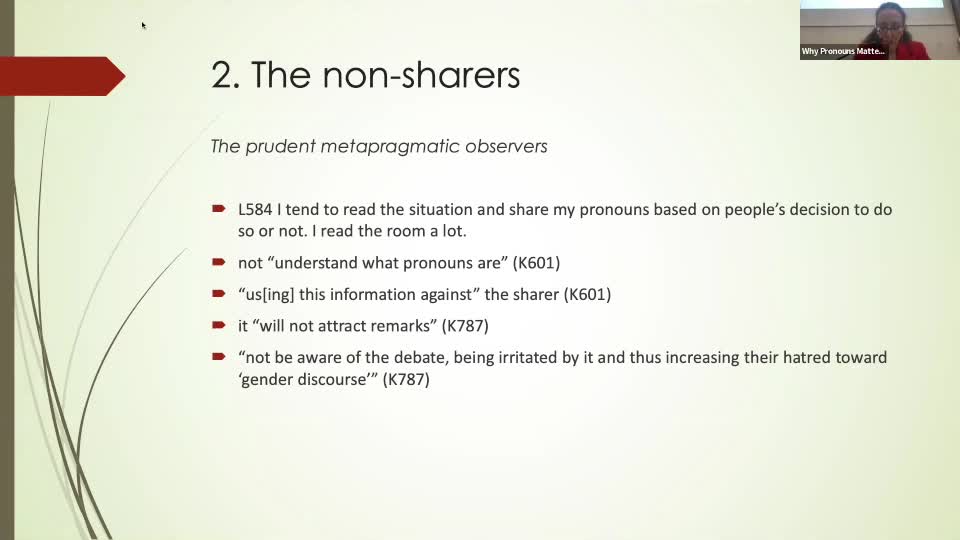

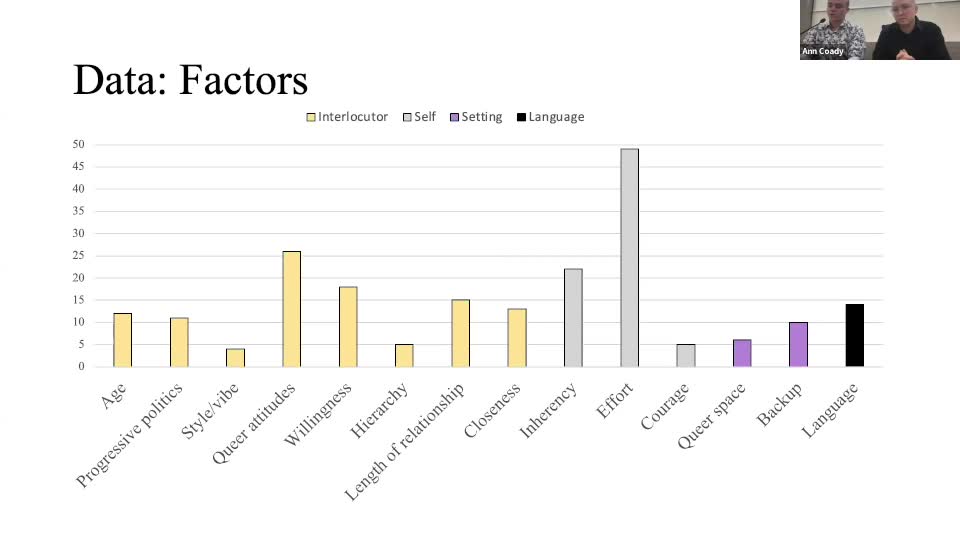

“Pronoun sharing and stancetaking: political and cultural (dis)alignment”, Ann Coady, Université Pa…

I begin my presentation by putting current pronoun-sharing practices in political and theoretical context, briefly discussing the current political debate surrounding these practices and comparing

““What’s a she/they?”: An (auto)ethnographic exploration of epistemic justice and the double bind o…

In this paper, I combine autoethnographic reflections with an exploration of epistemic injustice (e.g. Berenstain, 2016; Davis, 2016; Fricker, 2007; Pohlhaus, 2014) to consider how the persistent

““Mein Name ist Lena und meine Pronomen sind she/her”: Exploring Indexicalities of Pronoun Sharing …

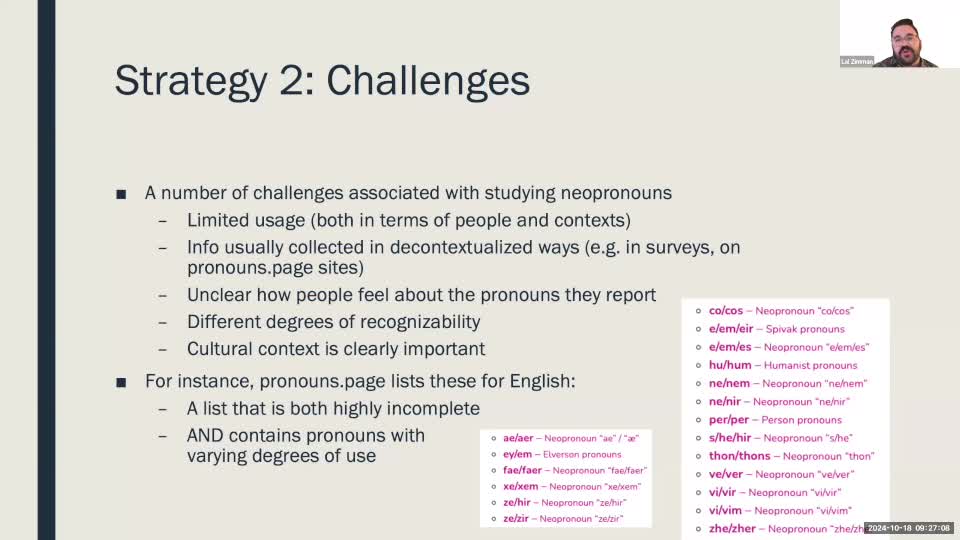

Since pronoun sharing has been associated with different political stances from virtue signaling to trans liberation, it is clear that they transport more information than simply how a person asks to

“What’s in a pronoun and how does it matter?: From the perspective of pragmatics”, Sandrine Sorlin,…

In this talk, I wish to give a quick overview of the quite recent ‘pronoun sharing’ trend from a linguistic and pragmatic perspective, going through the new collocations and semantic shifts of the

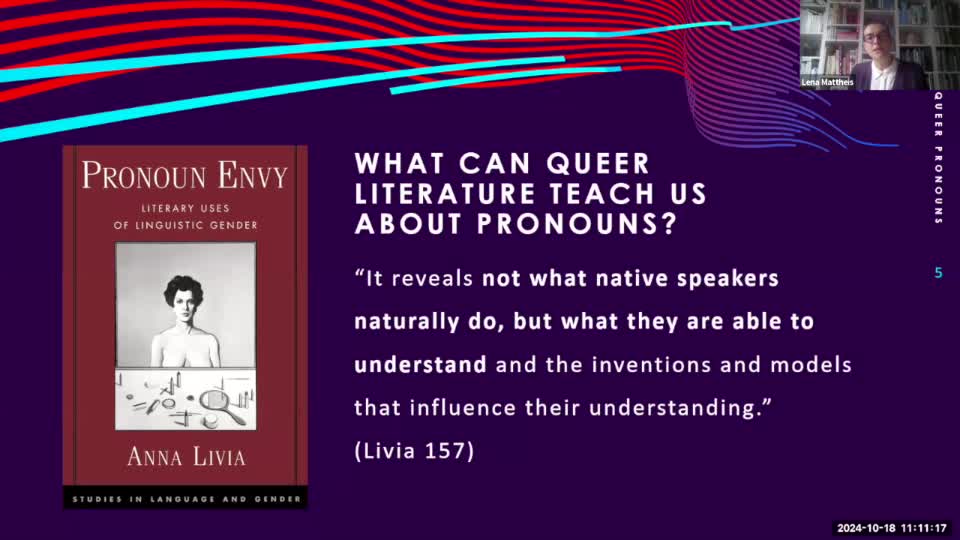

“Gendernonconforming Pronouns in Literature”, Lena Mattheis, University of Surrey, UK

Queerly reshaped pronouns, forms and narrative strategies are flourishing in contemporary non-binary, trans and queer literature. From singular ‘they’ to ‘it’ to neopronouns to the collective voice of

“Pronouns in Motion: Pronoun variability among Swiss non-binary individuals”, Justyna King and Elij…

Our paper aims to explore pronoun practices and flexibility among Swiss non-binary individuals, by elucidating the factors influencing the pronoun usage of Swiss non-binary people, discerning the

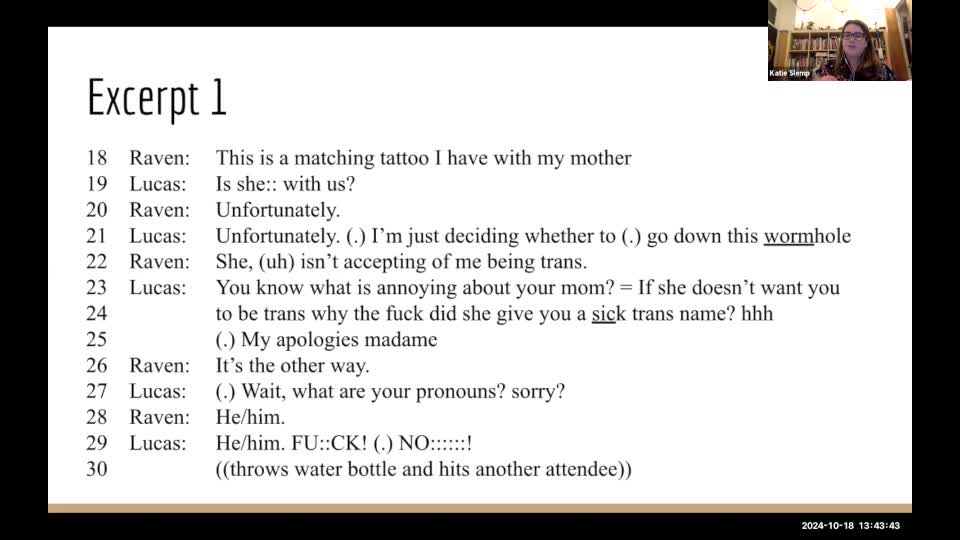

““Wait, what are your pronouns, sorry?”: Conversation analysis of pronoun requests in comedians’ cr…

Comedians on TikTok frequently show videos of their crowd work, where they ask questions to the attendees. While this is not part of their structured stand-up, it allows for spontaneous interaction

Intervenants et intervenantes

Doctor of philosophy, Philosophical Faculty, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf

Docteur en littérature anglaise (Montpellier 2, 1987). Professeur d'études américaines, université Paul-Valéry, Montpellier (en 2016)

Docteur en Langue et culture des sociétés anglophones. En poste à Aix-Marseille Université, LERMA/IUF (2018)