Notice

FMSH

Marina Costa-Lobo - Holding the EU Accountable through national legislative elections

- document 1 document 2 document 3

- niveau 1 niveau 2 niveau 3

Descriptif

Marina Costa-Lobo est chercheuse à l'institut des sciences sociales de l'université de Lisbonne. Elle nous parle de sciences politiques et de comportement électoral au Portugal et, plus généralement, en Europe.

Retrouvez la transcription intégrale de cet entretien dans l'onglet "DOCUMENTATION".

Intervention / Responsable scientifique

Thème

Documentation

Transcription

My name is Marina Costa-Lobo. I am a political scientist at the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon. The Institute of Social Sciences is a research institute, so mostly doctorates and researchers. My field of research is political science, more specifically, I have researched voting behaviour in Portugal, also in a comparative perspective. In particular, I have been the director of the Portuguese election studies; that is the post-election surveys that are implemented every time there is a legislative election in Portugal. This is a project that has been very long-standing and through which I have become really interested in electoral change in Portugal and in Europe. Throughout my research, I won an ERC grant in 2015. This grant was to study the way in which the eurozone crisis had an impact on the importance of Europe for voting in different countries. So the countries that I included in my project were countries that had suffered a bailout, including Portugal, but also Spain, Greece, Ireland. Those are the bailout countries and also some countries that had done relatively well in the eurozone crisis, namely Germany and Belgium. The whole project that I have been implementing in the last five or six years concentrates on these six countries to understand the degree to which Europe had become central to the national political debate, or not, following the eurozone crisis and whether this had had consequences on voting behaviour. We've done a lot in the project. I thought that in fact it would be very interesting to include France in the project because France is a case where it seems that Europe has become a very important topic. It distinguishes between Macron and Le Pen in 2017, but perhaps also in 2022, so I thought it would be very interesting to also include France. That's why I thought of trying to come here for a few weeks to speak to colleagues that are also doing electoral behaviour, namely in (inaudible) at Sciences Po, colleagues that some of them I already knew because I have met them in conferences, to see if I could get data on this issue of how Europe has become important for legislative elections in France to incorporate into my project. The goal of the project is to understand the effect of EU politicisation on voting behaviour in Europe. Why is this important? Well, coming from Portugal, it was very clear that the eurozone crisis was kind of a turning point in the way that Europe was discussed because Europe used to be kind of distant from everyday politics, but with the eurozone crisis and with the bailouts, suddenly Europe was very close; European institutions formed the troika alongside the IMF and there was a program which was implemented and people, citizens, really discussed this on a day to day basis. So it was very clear that Europe had a big impact on policy. I was interested to understand the degree to which this had an impact on voting behaviour. It comes from my Portuguese experience, but it's really a European experience because I think the crisis had an impact on different countries in different ways. So the point was to measure first how Europe had become important. So for that, we look at media and also parliamentary debates in the six countries. The second and related point, which is important, is that when people think about holding Europe accountable, because if you believe that Europe is very important for policies, then it's also important that people are able to hold Europe accountable. When this is normally researched, you normally focus on the European Parliament elections, not the national elections, right? Because the European Parliament is supposed to be the place where you can hold Europe accountable. The fact is that citizens, still today, don't really look at the European Parliament as the main forum for holding Europe accountable. In fact, people still look at the national institutions, mainly. What mattered to me is to see the degree to which Europe as an issue had become important at the national level, because for citizens, it continues to be the main level of accountability and where people focus when they think about politics. So I wanted to focus on the national level. We produced data on the media and parliamentary politicisation over time, and then we used that to understand whether this information environment, with more emphasis on the EU, has an influence on how people vote. So what we mean by politicisation is that there are many topics that can be politicised in the sense that they can become contentious, they can be divisive, but not all topics are divisive. So for a topic to be divisive and to be politicised, the topic needs to be salient; it has to be discussed by a lot of people in the media, also in Parliament. But also the topic needs to split parties; you have to have parties on one side of the question and on the other side of the question. So it has to be polarised; that's the definition of politicisation; it's the combination of salience with polarisation; we measure that, both in the media and also in parliaments. It's very easy to measure salience, it's very difficult to measure polarisation. What we found was that, in the media, salience and polarisation correlate in the sense that, as salience grows, polarisation also grows, and in particular, negative positions become much more frequent. So this is about this tendency that exists in the media, which is a negativity bias; when the media talks a lot about something, they are normally saying bad things about it. So we confront that with our data; that also means that you only need to measure salience in the media. And then you can presume that as it increases, the negativity is also going to increase. But in the parliamentary debates, it's not like that. The parliamentary debates is when there is salience, it's not really because the EU issue is not polarised. So the main parties, they will speak about Europe if there is no extreme party that is Eurosceptic. So they are very comfortable there and speaking about Europe and it's all very pro-EU and it's salient, but it's not polarised. If there is polarisation in the Parliament, then the mainstream parties will speak less about Europe. Why? Because we assume that they don't want to give the floor to the Eurosceptic parties so that they can gain salience themselves from that issue. So in parliamentary debates the correlation is negative between salience and polarisation, which I think is quite interesting because these forums are happening at the same time, but they don't have the same logic. I wanted to say another thing, because then we look at votes, we use a lot of different methods and we consider how the EU matters for voting, and it does matter. We already knew that the EU matters for people who vote for populist parties. We know that the populist parties on the right, they are Eurosceptic, sometimes on the left they are also Eurosceptic, and this issue matters. But what we also found is that the EU also matters for people who vote for the mainstream parties. So it's not just for the Eurosceptic voters; in the centre people also use what they believe about the EU to vote. So this is a sign that it is becoming more important, not only for the voters of the populist parties, but of the other parties. Issue voting: it is an issue that is significant and it's significant in all of the countries, and that's already saying something because it's very rare that an issue is important in a group of countries. But what happens is that the position of the individual in the left-right scale is normally very predictive of the vote. But the European issue is not very easily represented by the left-right scale because there are parties on the left and parties on the right that are Eurosceptic. So it cross cuts rather than reinforces the left-right cleavage. This is something that we saw, right? So it is an issue that matters. It's an issue that cross-cuts the left-right issue. There is a big debate in European political science on whether this European issue is kind of replacing left-right, say, for instance, between those who are pro-EU, cosmopolitan, pro-globalisation, etc., versus those who are Eurosceptic, nationalist and anti-globalisation, and this cleavage would replace the left-right cleavage. We don't find that. What we find is a very big resilience of the left-right cleavage. In terms of relative importance, I would say left-right continues to be the main reference, the main cleavage. But the EU issue is there. It's relevant not just for populist, but also for mainstream parties, but in the countries that we have, it's not replacing the left-right. I think that the use of my project, and this is something I tried to write in the book that I've edited with my colleagues, and that will come out in 2023; it's really about this idea that it's possible to hold the European Union accountable nationally. When all is considered, what I think the message is, is that there is a great degree of politicisation at the national level. People are getting information, when they vote at the national level they are also including their preferences about the European Union when they select. So they are looking at the positions of the parties at the national level in relation to the EU and making their choices. This has a message for the debate about democracy in Europe because a lot of people, when they discuss democracy in Europe, they only consider reforms of the European Parliament. But in fact, what my book is suggesting is that national parliaments are very important and should be valued because accountability of the EU is processed through these national institutions. So if we wanted to understand there is this emergence of populism in the context of the politicisation of Europe, I would say the following: we know that populist parties play the Eurosceptic card, correct? So they are politicising Europe. They are not the only ones politicising Europe today, but one of the main causes of EU politicisation are these parties. When we speak about populist parties, they can be either from the left or from the right. It's interesting because, when we consider Europe, they politicise Europe in different ways. The right will politicise Europe more on values, culture and the fact that there is immigration through Schengen, etc. whereas the Left politicise the Euroscepticism more about the issue of globalisation that exists because of the EU, open markets, the problem of national production, etc.; it's much more of an economic argument rather than a cultural argument. I think that a lot of research has shown that these two dimensions coexist in the support for populist parties. So their rise, their emergence among the electorate has to do with economic reasons, but also cultural reasons. A lot of the cultural reasons can also be explained because of economic issues. So I think that there is a lot of economic reasons of people feeling that they are losing out from the European integration process, that they are not able to fulfil their expectations in terms of standard of living, that then leads to these votes. So I think that there has been a change in Europe with the next generation funds that were organised after the pandemic. This is a very interesting development in the sense that, in the eurozone crisis, when there was the eurozone crisis, the message was each country has to deal with the problem either through a bailout or through austerity policies, the EU can really do nothing about it. But with the pandemic crisis and there has been really a change of message and a change of substance in the sense that the origin of the problem was different because there was really a problem that was exogenous, the pandemic is exogenous to all countries and all countries suffered, and so the EU's response was completely different; there was the creation of EU bonds, and there was the creation of a big program to help avoid another ten years of austerity. All this to say that I think that the message has gotten through to the EU that populism is a result, to a large degree, of economic problems that the EU should be worried about and that they should contribute to solve. Of course, it's not the whole story. There are cultural issues and there are also political issues, namely the fact that people would like to be more involved in politics or they feel politics is very distant. This is something that the EU has to think about very carefully. But again, this issue of the national institutions being relevant I think is also contributing to that.

Sur le même thème

-

GePat-FP : Gestion du patrimoine privé et situations d’extranéité franco-portugaises

Labelle-PichevinFabienneLes circulations de biens et de personnes entre la France et le Portugal se sont intensifiées au XXe siècle par suite d’une vague d’immigration des portugais vers la France liée à un contexte politico

-

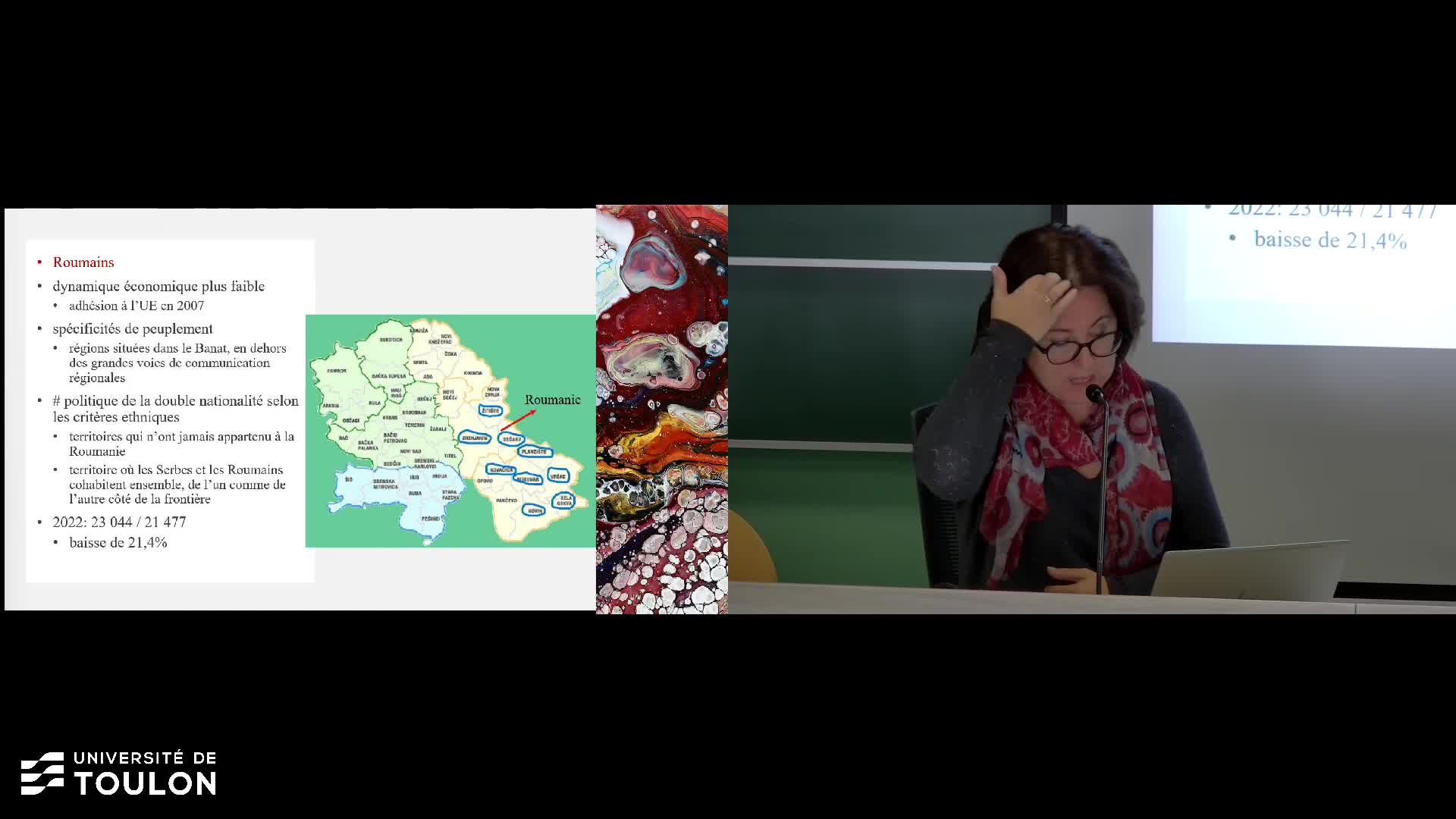

Une région qui pose des défis aux notions de territoire et de frontière : la Voïvodine (Serbie)

DjordjevićKsenijaLa situation géopolitique actuelle met au cœur de l’actualité la notion même de territoire et la pluralité des modes de rapport d’une population à son territoire, imposant de revenir aux fondamentaux

-

MARIO SOARES L'EXIL D'UN DEMOCRATE PRO-EUROPEEN

VasconcelosÁlvaro deSoaresIsabelAraujoChristopheMartinsGuilherme d'OliveiraMorinEdgarLe 25 avril 2024 marquera le 50e anniversaire de la révolution des Œillets qui a mis fin à 48 ans de dictature et d'empire colonial, tout en déclenchant une vague démocratique en Europe et dans le

-

Vingt ans après l’élargissement de 2004. L’état des libertés en Europe centrale et orientale

HeurtauxJérômeGoujonAlexandraGaconJulieLa table ronde "Vingt ans après l’élargissement de 2004. L’état des libertés en Europe centrale et orientale", s'est tenue le 23 mai 2024 au Forum de la FMSH

-

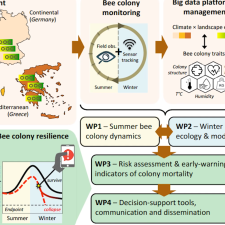

BeeConnected

BeeConnected, projet européen étudie, développe et teste de nouvelles solutions numériques pour fournir des indicateurs d'alerte précoce sur la mortalité des colonies d'abeilles mellifères.

-

Pirates et corsaires en Méditerranée occidentale (XIVe-XVe siècles)

GouffranLaure-HélèneLa maîtrise du bassin occidental de la Méditerranée fait l’objet d’une vive concurrence au Moyen-Âge (XIIe-XVe siècles) entre les royaumes de l’Europe méridionale. La situation de Marseille en fait un

-

Les Rencontres de l'Institut Européen des Jardins et Paysages

MartellaMarcoBenechLouisSijmonsDirkCastel-BrancoCristinaRencontres du 15 février 2024

-

Perception et appréhension du risque naturel à l'Antiquité et au Moyen Âge (Parama)

Dumasy-RabineauJulietteLe projet PARAMA est un projet historique, archéologique et environnemental ayant pour but d’étudier la perception et l’aménagement des milieux spécifiques (humides, montagnards et forestiers) face au

-

EOSC au CNRS 2024 : discours d'ouverture

El KhouriLaurenceJournée EOSC au CNRS 2024 - Discours d'ouverture avec Laurence El Khouri (DDOR, CNRS)

-

Dimension scientifique : vision et objectifs de l'EOSC

DumouchelSuzanneJournée EOSC au CNRS 2024 - Dimension scientifique : vision et objectifs de l'EOSC avec Suzanne Dumouchel (DDOR, CNRS)

-

Dimension technique : architecture et structure de l'EOSC

RouchonOlivierPansanelJérômeJournée EOSC au CNRS 2024 - Dimension technique : architecture et structure de l'EOSC avec Jérôme Pansanel (Unistra) et Olivier Rouchon (DDOR, CNRS)

-

EOSC : état des lieux

DumouchelSuzanneJournée EOSC au CNRS 2024 - EOSC : état des lieux avec Suzanne Dumouchel (DDOR, CNRS)