Notice

Travels with Hanna: Dogs and/as Teachers / Scott Slovic

- document 1 document 2 document 3

- niveau 1 niveau 2 niveau 3

Descriptif

Travels with Hanna: Dogs and/as Teachers / Scott Slovic, conférence plénière in colloque international "L'Amour des animaux / Animal Love", organisé par leLaboratoire Cultures Anglo-Saxonnes (CAS), la Sociétéd’Étude de la Littérature de Voyage du monde Anglophone (SELVA), l'Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et BellesLettres (ASIBL)de Toulouse, sous la responsabilité scientifique de Françoise Besson (CAS,SELVA, ASIBL), Marcel Delpoux (ASIBL, SELVA), Nathalie Dessens (CAS) et ScottSlovic (SELVA, University of Idaho, USA). Toulouse, Hôtel d'Assézat, Hôtel duMay, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, 20-23 mars 2019.

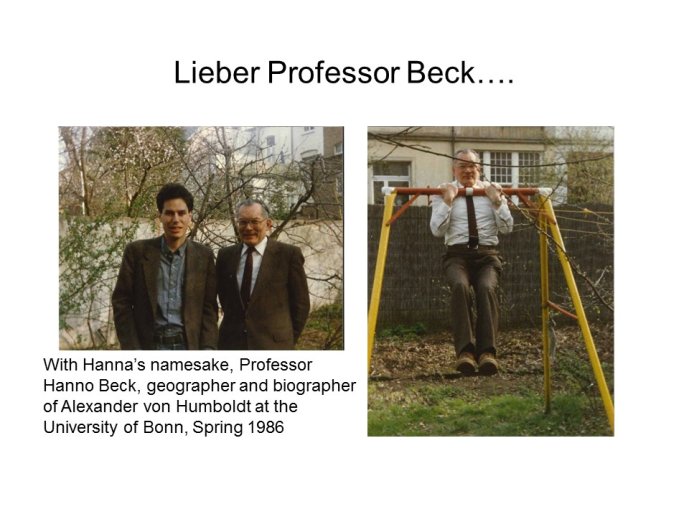

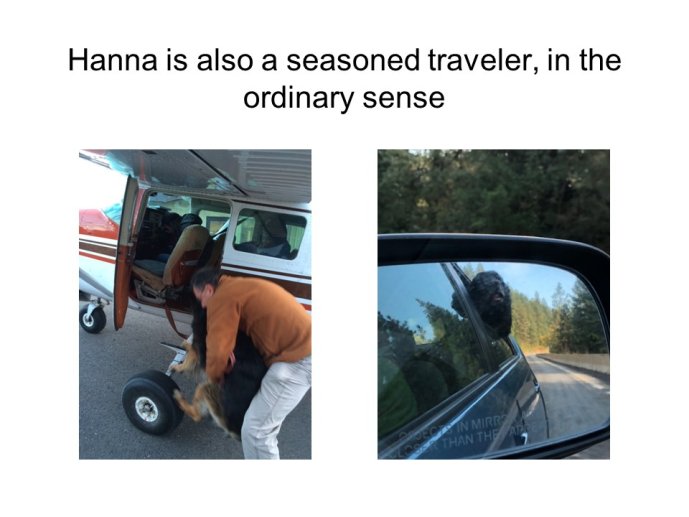

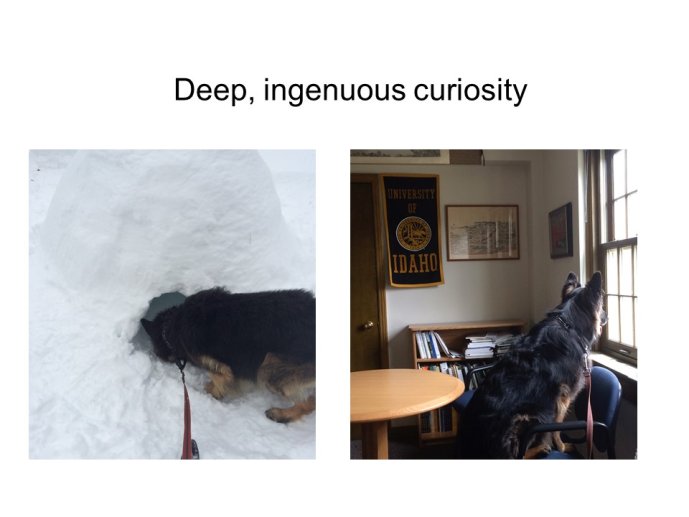

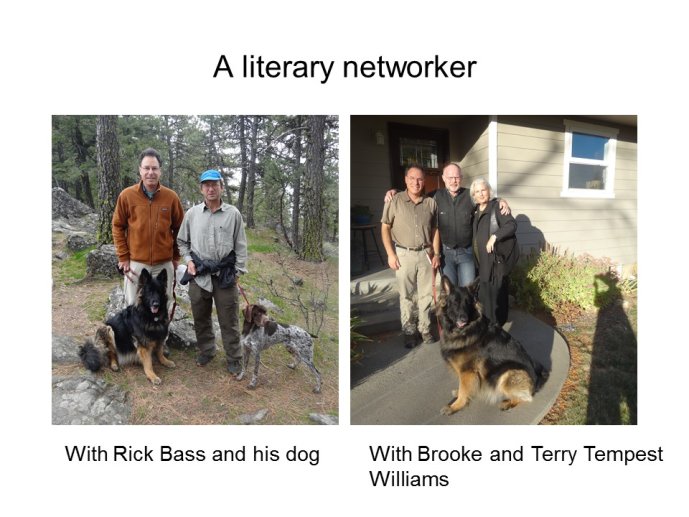

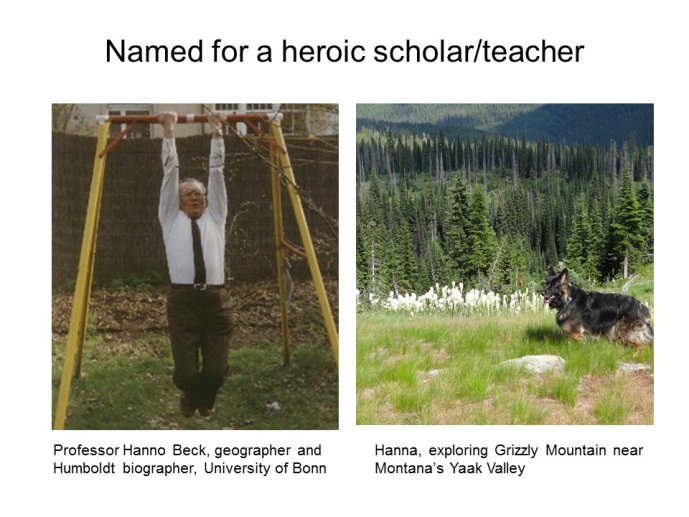

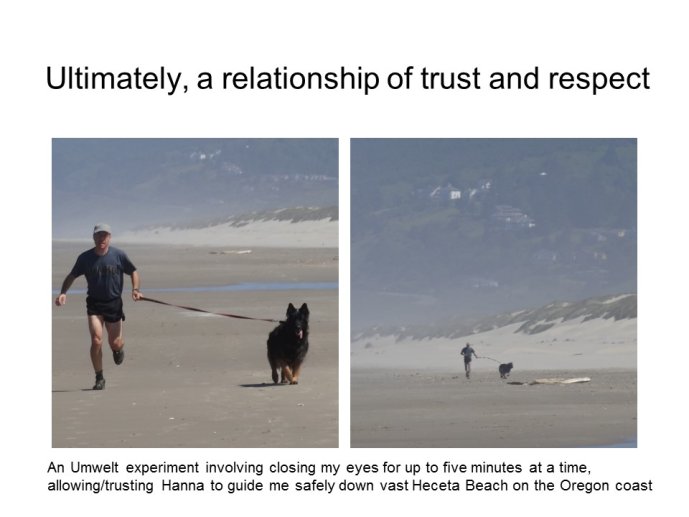

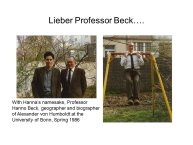

In September 1960, just over fifty-eight years ago and three months after I was born, fifty-eight-year-old John Steinbeck set off from his home in Sag Harbor, New York, to drive across the United States and back with his French poodle Charley for company. Steinbeck published his travelogue "Travels with Charley in Search of America" in 1962, the same year he received the Nobel Prize in Literature, but despite its title, the book is mostly a curmudgeonly analysis of American culture during a time of tumultuous change, with Charley merely along for the ride, providing a calming diversion for the writer. “I came with a wish to learn what America was like,” says Steinbeck. “And I wasn’t sure I was learning anything. I found I was talking aloud to Charley. He likes the idea but the practice makes him sleepy.” During a time of comparable tumult and tension in American culture, I turn in 2019 to my eight-year-old German Shepherd named Hanna for distraction from politics and insight into human nature. Named after Professor Hanno Beck, the eminent scholar of Alexander von Humboldt and my Fulbright host many years ago at the University of Bonn, Hanna is my companion on several walks and runs every day, frequently travels with me on long cross-country drives and sometimes even by small airplane when I teach students in the Idaho wilderness, and lies near my table when I’m writing. Shortly after my wife and I adopted Hanna, I read Alexandra Horowitz’s best-selling book "Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know" (2009), and with Horowitz’s insights into dog perception and epistemology in mind, I have spent the past eight years watching Hanna engage with the world. She is not only my companion, but, in a very real sense, my teacher—I learn about the world and about myself by watching and interacting with her. In this presentation I will compare my own experiences “traveling with Hanna” with Steinbeck’s writing about Charley and the state of the world, and I will share some of the lessons I’ve gleaned from my time with her.

___

Le but de ce colloque est d’envisager l’amour des animaux, l’amour animal, l’amour pour les animaux dans sa multiplicité et sous un angle à la fois philosophique, scientifique, littéraire et artistique et en inscrivant ce thème dans la relation plus large de l’homme au monde et dans la vision environnementale et écocritique. Des espèces compagnes à la relation (l’amour ?) des animaux pour des membres de leur propre espèce ou d’espèces différentes, l’expression “l’amour des animaux” est polysémique. On pense à l’amour des chiens et chats pour leur compagnon humain et à la relation réciproque de l’attachement humain pour ces êtres non-humains qui accompagnent leur vie, au chien qui accompagne son ami humain jusqu’à la tombe et va y rester des jours et parfois se laissera mourir. Que dire de ce chat américain qui dans un hôpital, va dans les chambres de malades dont il perçoit avant les médecins qu’ils vont mourir bientôt et les accompagne jusqu’à leur dernier souffle ? Comment définir son rôle gratuit et étrange d’accompagnateur qui va leur permettre le passage en leur offrant une présence amie et rassurante ?

L’amour des animaux, c’est à la fois l’amour de l’être humain pour le monde animal, l’amour -ou tout autre sentiment auquel il conviendra de réfléchir- de l’animal pour l’être humain et l’amour des animaux entre eux ; l’amour pour tout souffle de vie ; l’amour de la chatte pour ses petits, le geste de l’hippopotame tentant de sauver l’antilope de la gueule du crocodile, les soins d’une bande de chats des rues en Argentine sauvant un enfant perdu en lui apportant de la nourriture et en le réchauffant jusqu’à ce qu’il soit retrouvé. Est-ce de l’amour ? Est-ce un instinct de survie ? Une empathie inexplicable ? Comment définir la notion d’amour des animaux ? Ces gestes de tendresse, de compassion ou d’empathie du monde animal peuvent-ils être rattachés à l’amour ou sont-ils des gestes instinctifs de sauvetage de quelque espèce que ce soit visant à prolonger la présence animale sur la terre ?

The aim of this conference is to consider animal love in its multipicity, from a philosophical, scientific and literary angle at the same time, by inscribing the theme in the wider relationship of man with the world and in the environmental and ecocritical vision as well. From companion species to the love of animals for members of their own species or of other species, the phrase “animal love” is polysemous. We first think about the love dogs and cats have for their human companions and about the reciprocal relationship of attachment of human beings for those nonhuman companions accompanying parts of their lives; we can think about the dog following his human companion’s coffin and accompanying him/her to the grave, staying there days and nights and sometimes dying there. What can we say of the American cat who, in a hospital, goes into dying people’s rooms, knowing before doctors that those people are going to die and accompanying them until their last breath? How can we define her gratuitous, strange role as a companion, allowing them to pass away while offering them a friendly, reassuring presence?

Animal love is both the human being’s love for an animal or several animals and the love—or any feeling we could associate with love—of the animal for the human being and the love of animals for one another. Can we consider the gesture of a hippopotamus for the antelope that he tries to rescue from the crocodile’s teeth, staying with her head in its mouth until her last breath, as love? What about the behaviour of a group of street cats in Argentina, who saved a lost human infant by giving him food and lying on him so that he did not die of cold in the night, until the day when he was found. Is this love? Is it some survival instinct shared with those who are threatened? Is it some unexplainable empathy? How can we define the notion of animal love? Could those gestures of apparent tenderness, compassion or empathy of the animal world be qualified as love—could they be linked with love or are they instinctive rescuing gestures made by whatever species to prolong the animal presence on the Earth?

Thème

Documentation

Bibliographie sélective

> Voir la bibliographie (à télécharger en pdf) dans l'onglet "Documents".

Dans la même collection

-

Animal Cause. Contemporary Chalenges in Brazilian Society / Zelia Monteiro Bora

BoraZélia MonteiroAnimal Cause. Contemporary Chalenges in Brazilian Society / Zelia Monteiro Bora, conférence plénière in colloque international "L'Amour des animaux / Animal Love", organisé par le Laboratoire

-

Le chien truffier dans sa relation affective avec l'homme, son maître, son ami / Pierre Sourzat

SourzatPierreLe chien truffier dans sa relation affective avec l'homme, son maître, son ami / Pierre Sourzat, conférence plénière

-

Toward werewolf diplomacy: Cross-species kinship and ecopoetics in "Animal Dreams" and "Prodigal Su…

MeillonBénédicteToward werewolf diplomacy: Cross-species kinship and ecopoetics in "Animal Dreams" and "Prodigal Summer" by Barbara Kingsolver / Bénédicte Meillon

-

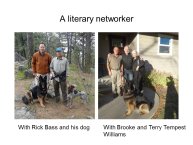

"Brown dog of the Yaak" and "Colter" by Rick Bass or a tribute to human-dog companionship / David L…

LatourDavidBrown dog of the Yaak and Colter by Rick Bass or a tribute to human-dog companionship / David Latour

-

L'homme et le chat : une histoire et un avenir communs ? (Des origines à l'Intelligence artificiell…

VercruyceBernardL'homme et le chat : une histoire et un avenir communs ?

-

Animaux réels et fantastiques dans l'art médiéval de la région Occitanie / Guy Ahlsell de Toulza

Ahlsell de ToulzaGuyAnimaux réels et fantastiques dans l'art médiéval de la région Occitanie / Guy Ahlsell de Toulza

-

De la raison à la passion pour les dinosaures et l'énigme des grandes extinctions / Marcel Delpoux

DelpouxMarcelDe la raison à la passion pour les dinosaures et l'énigme des grandes extinctions / Marcel Delpoux, conférence plénière

-

Amour-Haine ou l'ambiguïté de la relation serpentine / Pierre Lile

LilePierre C.Amour-Haine ou l'ambiguïté de la relation serpentine / Pierre Lile

-

Les loups et les ours : une histoire d'amour difficile

López MújicaMontserratpar Montserrat López Mújica

-

Le siècle de "Winnie l'Ourson" / Yves Le Pestipon

Le PestiponYvesLe siècle de Winnie l'Ourson / Yves Le Pestipon, conférence plénière

-

L'amour offert aux animaux que l'on dresse : stratagème ou complicité ? / Olivier Courthiade

CourthiadeOlivierL'amour offert aux animaux que l'on dresse : stratagème ou complicité ? / Olivier Courthiade

Avec les mêmes intervenants et intervenantes

-

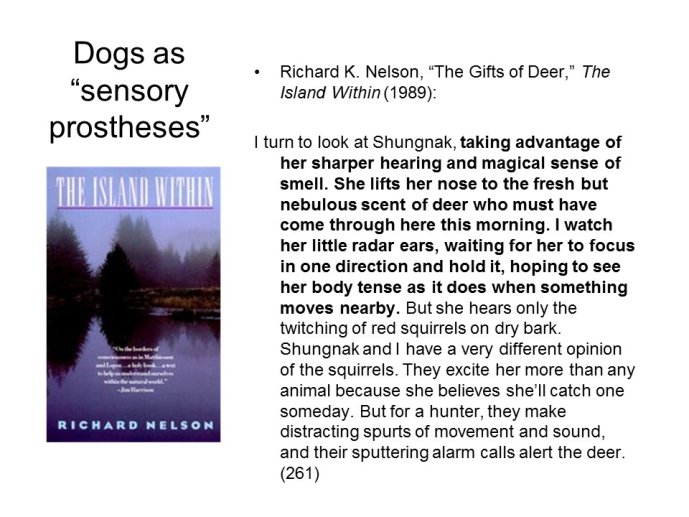

Dogs as Sensory Extensions of Self: A Gift / Scott Slovic

SlovicScottDogs as Sensory Extensions of Self: A Gift / Scott Slovic, Keynote in International Symposium "Companion Species in North American Cultural Productions", organisé, sous la responsabilité scientifique

-

The World of Scholarly Publishing: a Seminar Featuring / Scott Slovic

SlovicScottThe World of Scholarly Publishing: a Seminar Featuring / Scott Slovic. Séminaire en deux volets ("From Dissertation to Book" et "Conference Papers and Journal Submissions") organisé le 31 mai 2011 par