Notice

Semantics in the Time of Computing

- document 1 document 2 document 3

- niveau 1 niveau 2 niveau 3

Descriptif

Much of the technical terminology of computer science betrays its logical heritage: ‘language’, ‘symbol’, ‘syntax’, ‘semantics’, ‘value’, ‘reference’, ‘identifier’, ‘data’, etc. Classically, such terms were used to name essential phenomena underlying logic, human thought and language — phenomena, it was widely believed, that would never succumb to scientific (causal, mechanical) explanation. Computer science, however, now uses all these terms in perfectly good scientific ways, to name respectable scientific (causally explicable, mathematically modellable) phenomena.

There are two possibilities. The first is that computer science has given us a scientific understanding the fundamental mysteries of language, logic, and mind. The second is that computer science has redefined these words, so that, although they have been brought into the realm of the scientific, they no longer refer to what they used to refer to. Most people believe the former. I will argue for the latter: that, for reasons traceable back to Turing’s 1936-7 paper, computer science has redefined these terms in such a way as to “disappear” much of what is fundamental to the human condition: language’s long-distance reach, the “non-effectiveness” of truth and reference, thought’s normative deference to the world.

The result, I believe, not only challenges prospects for Artificial Intelligence and cognitive science, but also limits our ability to understand data bases, knowledge representation, even programs. It also hinders communication, because overlapping technical vocabulary means different things in different communities. Most seriously, it undermines our ability to talk about the most fundamental aspects of semantic or symbolic systems.

Thème

Sur le même thème

-

Loterre : Des terminologies en partage

Loterre (Linked open terminology resources) est une plateforme d’exposition et de partage de terminologies scientifiques multidisciplinaires et multilingues, conforme aux standards du web des données

-

Topics in aspectuo-temporal expression in Anindilyakwa

BEDNALL James

This presentation examines temporal and aspectual expression in Anindilyakwa, a language whose inflectional verbal system displays both a complex morphological makeup, and a largely underspecified

-

Co-reference in (linguistic-)pictorial discourse

ALTSHULER Daniel

This talk takes up the question of how one arrives at pragmatic interpretations of pictorial and mixed linguistic-pictorial discourses.

-

[jeu de maux] épisode 1. L'étymologie / la terminologie du suffixe -rrhée et la diarrhée

GUERRIAUD Mathieu

[Jeu de maux] épisode 1. L'étymologie / la terminologie du suffixe -rrhée et la diarrhée

-

La nominalisation : fait de langue ou fait de style ?

Cette communication entend s'interroger sur une des questions posées par le colloque : [comment un fait de langue peut-il devenir fait de style ?]. La question sera examinée à partir d'un corpus d

-

Faits de langue, de discours et de style. Etude à partir des définitions de psychomécanique

La psychomécanique du langage établit une distinction entre le fait de langue et le fait du discours. Ce qui est de l'ordre du discours est un ensemble de « faits momentanés » dont la linguistique

-

Mirative extensions in the postmodal domain

The aim of this paper is to offer a semantic-pragmatic account of the postmodal uses of should and would. Arguably, should and would are related to the postmodal domain in so far as both modal

-

Modal meanings become discourse-oriented

Van der Auwera and Plungian’s (1998) map of possibility and necessity paths offers a re-arrangement of Bybee et al. (1994)’s data on grammaticalization paths in the domain of modality along two

-

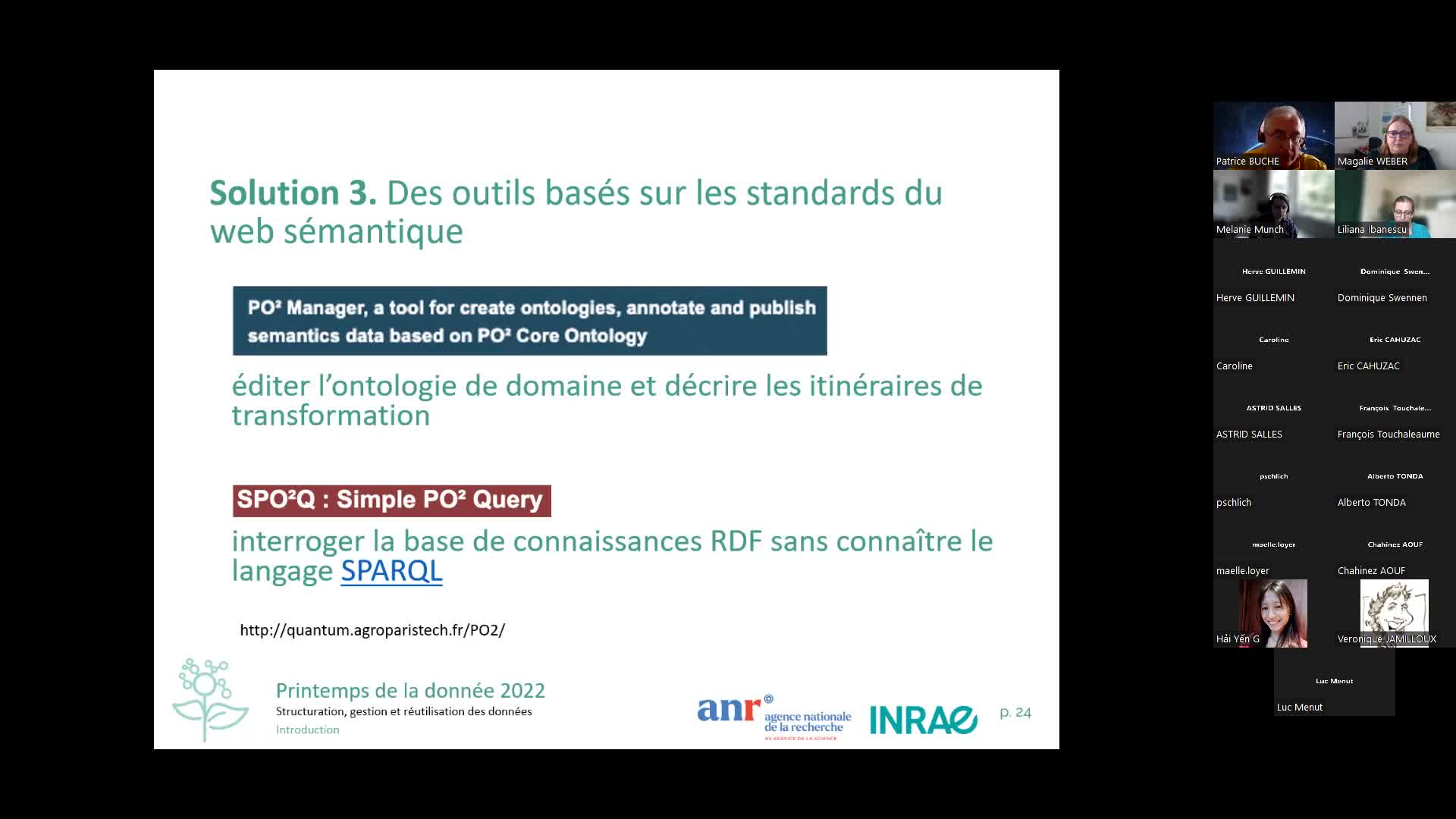

Prototype de pipeline PO²-réseaux bayésiens pour l’aide à la formulation d’emballages biocomposites

Webinaires du département Transform – Ontologie et base de données PO² – 1/4

-

Documents, Textes, Œuvres

François Rastier souhaite synthétiser des acquis de l'herméneutique et de la philologie pour promouvoir une sémantique des textes historique et comparée, appuyée sur la linguistique de corpus. Son

-

Transcrire sans dessiner les sceaux. Quel sens donner à cette démarche? (France de l’Ouest, XIe-XII…

A partir de la fin du XIe siècle, l'usage du sceau se répand dans le Val de Loire tout en cohabitant avec d'autres formes de validation des actes. Son emploi s'intensifie au XIIe siècle. En revanche,

-

L’interopérabilité sémantique au service de la réutilisation des données SHS : OntoME et le projet …

ALAMERCERY Vincent

BERETTA Francesco

Nous avons tous des vieux fichiers au fond d’un disque dur comportant des données plus ou moins structurées de l’époque héroïque où les chercheurs en sciences humaines utilisaient vaillamment des

![[Jeu de maux] épisode 1. L'étymologie / la terminologie du suffixe -rrhée et la diarrhée](https://vod.canal-u.tv/videos/2024/07/99220/jeu_de_maux-diarrhee.jpg)