Notice

Harry Potter and the cross-linguistic semantics of tense and aspect

- document 1 document 2 document 3

- niveau 1 niveau 2 niveau 3

Descriptif

Stories are typically told in the past tense (Fleischmann 1990), but next to narrative discourse, novels sometimes contains dialogue parts, as in the following example from J.K. Rowling’s (1998) novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone :

"Well?" said Quirrell impatiently. "What do you see?"

Harry screwed up his courage.

"I see myself shaking hands with Dumbledore," he invented. "I -- I've

won the house cup for Gryffindor."

In fictional dialogue (the parts in italics), the characters talk to each other about ongoing events, plan actions for the future and reflect on what happened in the past. Communication verbs (underlined in the Harry Potter example) anchor the parameters of the fictional utterance event (speaker, hearer, time). This talk exploits parallel corpus data to determine cross-linguistic similarities and differences in the distribution of tense-aspect forms between narrative discourse and fictional dialogue. The data come from Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and its translations into a range of Western European languages. The data have been collected through Translation Mining, a methodology that presents formal patterns of language use across languages as a source of cross-linguistic semantic evidence. The parallel corpus data reveal the language-specific mappings from tense-aspect forms to contextualized meanings, which serve as the input to a cross-linguistically robust semantics.

The Harry Potter dataset presented in Tellings et al. (2022) reveals different patterns of tense use. As expected under Fleischmann’s generalization, PAST tenses dominate in narrative discourse, but fictional dialogue displays a much wider range of PAST, PRESENT and FUTURE tenses. This holds for the English original as well as its French, Italian, Spanish, German, Swedish and Dutch translations. The data are reminiscent of early observations by Wunderlich (1970), Martin (1971) and Vet (1980) about two subsystems, one centred around the speech time, the other around a time in the past.

Partee (1973, 1984) argued that the English Simple Past is anaphoric in nature, and since then, must focus has been placed on tense and aspect in narrative discourse. The intricate patterns of temporal anaphoricity, the role of lexical, compositional and grammatical aspect, and the relations between rhetorical and temporal structure in narrative discourse have been analysed by Kamp & Rohrer (1983), Kamp & Reyle (1993), Lascarides & Asher (1993), Vet & Molendijk (1986) and others. The cross- linguistic patterns of tense use in the narrative discourse parts of Harry Potter display the grammatical and lexical aspect patterns predicted by the current literature, and thereby confirm the robustness of the Translation Mining methodology for cross-linguistic research.

The presence of PAST, PRESENT and FUTURE verb forms in fictional dialogue suggests deictic anchoring to an embedded utterance situation, and thereby highlights the inherently deictic nature of tense (Reichenbach 1947, Vet 1980). Fictional dialogue displays key features of direct speech, so the parallel corpus data from the dialogue parts of Harry Potter thus serve as a window on the cross- linguistic grammar of the spoken language. The cross-linguistic variation in the dialogue parts of Harry Potter replicates the competition between the HAVE-PERFECT and the (PERFECTIVE) PAST we found earlier in the French novel L’Étranger (van der Klis et al. 2022, Le Bruyn et al. 2024). Crucially, the (PRESENT) PERFECT is restricted to the dialogue parts of Harry Potter, even in liberal PERFECT languages like French, Italian and German. This finding has consequences for the aoristic drift, the diachronic process in which PERFECT forms acquire past meanings. Not only are there different paths along the aoristic drift (Corre et al. 2023), the restriction to the spoken language grammar suggests that the French Passé Composé and the German Perfekt have not reached the status of an aoristic past.

Intervention / Responsable scientifique

Dans la même collection

-

Narrating in a radically tenseless language

BertinettoPier MarcoThe activity of narrating is a fundamental element of social cohesion and is inherently based on the temporal dimension in which human events are couched. Furthermore, an events’ narration is

-

Temporality, Orality and Discourse Structuring

CarruthersJaniceIn the first part of this paper I will present some of the results of a Horizon 2020-funded project on temporality in Occitan and French oral narrative, undertaken in partnership with Marianne Vergez

-

Topics in aspectuo-temporal expression in Anindilyakwa

BednallJamesThis presentation examines temporal and aspectual expression in Anindilyakwa, a language whose inflectional verbal system displays both a complex morphological makeup, and a largely underspecified

-

Co-reference in (linguistic-)pictorial discourse

AltshulerDanielThis talk takes up the question of how one arrives at pragmatic interpretations of pictorial and mixed linguistic-pictorial discourses.

Sur le même thème

-

"Double modal constructions in Australian and New Zealand English: A computational sociolinguistic …

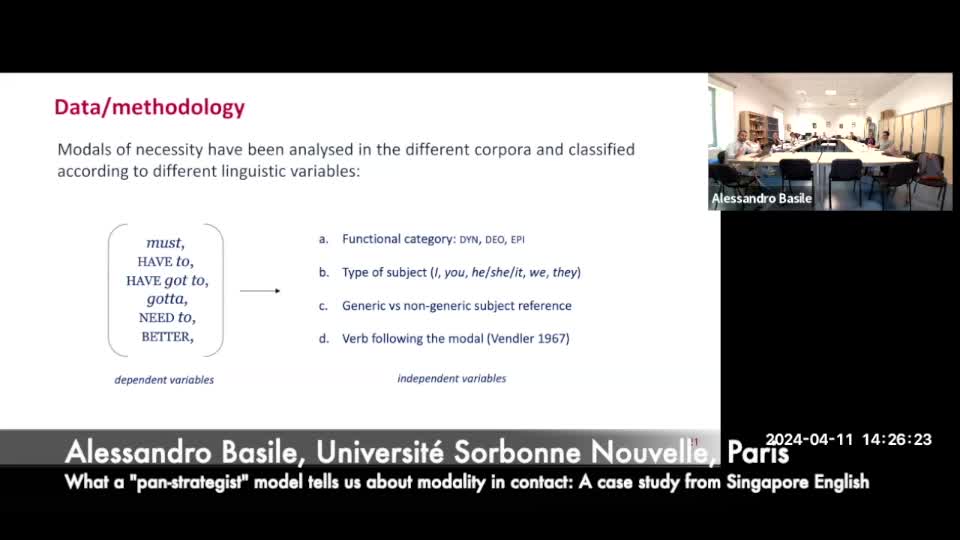

MorinCameronIn this presentation, I report the first large-scale corpus study of double modal usage in Australian and New Zealand Englishes, based on a multi-million-word corpus of geolocated automatic speech

-

"What a “pan-stratist” model tells us about modality in contact: A case study from Singapore Englis…

BasileCarmelo AlessandroThis talk aims to explore the development of a set of modal constructions of necessity and strong obligation, namely must, have to, (have) got to, gotta, need to, and better, in the contact variety

-

Archivo de la voz y de la subjetividad en la poesía contemporánea latinoamericana

FoffaniEnriqueLe colloque TransVersales. État(s) provisoire(s) de la poésie latino-américaine contemporaine se proposait de faire émerger et d’analyser des questions toujours essentielles comme le rythme, le

-

Narrating in a radically tenseless language

BertinettoPier MarcoThe activity of narrating is a fundamental element of social cohesion and is inherently based on the temporal dimension in which human events are couched. Furthermore, an events’ narration is

-

Temporality, Orality and Discourse Structuring

CarruthersJaniceIn the first part of this paper I will present some of the results of a Horizon 2020-funded project on temporality in Occitan and French oral narrative, undertaken in partnership with Marianne Vergez

-

Topics in aspectuo-temporal expression in Anindilyakwa

BednallJamesThis presentation examines temporal and aspectual expression in Anindilyakwa, a language whose inflectional verbal system displays both a complex morphological makeup, and a largely underspecified