Chapitres

Notice

Prix Charles et Monique Morazé 2014 - Mala SINGH

- document 1 document 2 document 3

- niveau 1 niveau 2 niveau 3

Descriptif

Le Prix Charles et Monique Morazé, remis par la Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme pour la deuxième fois, a été créé pour distinguer des travaux portant sur deux grands thèmes : éducation et société d’une part ; sciences et société d’autre part.

Le Prix 2014 est attribué à Madame Mala SINGH, professeur à la Rhodes University de Grahamstown, Afrique du Sud.

A l’occasion de la cérémonie de remise du Prix, le professeur Mala Singh a donné une conférence intitulée : "Re-thinking Knowledge and Social Change" - "Savoir et changement social : une relation à repenser".

>> Accès aux informations sur le site de la FMSH, cliquez ici

------

In 2014 Professor Mala SINGH was awarded The Prize Charles and Monique Morazé, established recently by the Fondation Maison des sciences de l’homme, Paris, and granted in recognition of theinnovative work on the issues of Science and society on the one hand, Education and society on the other hand.

The Award Lecture is entitled "Re-thinking Knowledge and Social Change".

------

Abstract

The 20th anniversary of formal democracy in South Africa in 2014 has stimulated a great deal of often-quantitative accounting of achievements and shortcomings in creating a better society. The post-apartheid social change agenda upheld an ambitious normative vision for democratic inclusion and social justice but produced an ambivalent yield of benefit and disillusionment. So many more houses built and yet so many people still live in shacks. So many more school leavers entering universities and yet the participation rates in higher education remain low. So many more citizens afforded social welfare benefits and yet large-scale poverty and its ravages remain largely undented. Progress beyond the formalities of constitutional democracy as the chosen form of government, towards the goals of social justice and social cohesion, accountable governance, tolerance for critique and dissent, and towards a more rationally and normatively planned polity remain more difficult to gauge.

The two-decade anniversary has evoked much debate and reflection on the ambitious social change agenda adopted in 1994 and on its implementation modalities and outcomes. In the face of ongoing systemic inability to improve the material conditions of life of the majority of the population as well as weaknesses in institutionalizing a democratic culture, questions have been posed about the need to re-think not only the chosen social policies and their accompanying implementation strategies but in some instances even the underlying legitimating vision and goals. Such reflections are taking place in government, in civic organizations, in the media and in the universities. There has, for instance, been a long-standing debate about the need to transform the universities and the research system in the direction of greater equity and social responsiveness. A recent initiative to re-dedicate collective research effort to address poverty and inequality in response to government’s National Development Plan has highlighted the question of the role of knowledge and modes of involvement of academics and researchers in the social change agenda in South Africa. In the same reflective vein of assessment about the direction and results of change currently evident in many social sectors, it may be useful to analyze how the relationship between knowledge (and its producers and institutions) and society (and its sources of power) has been constructed and with what benefits and challenges.

In considering the unfolding social change agenda in South Africa and the intellectual engagement that sought to support it, this presentation attempts to track some of the evolving conceptions about knowledge for social change among social researchers, higher education and research institutions, and policymakers. What shifts and swings have there been in the patterns of intellectual engagement with state and non-state actors as addressees of socially useful knowledge and what lessons learned? Assuming that the notion of socially useful knowledge is already a kind of political and moral narrative, how has the tension between political engagement and scientific rigour been articulated and negotiated? And given the legacies of apartheid exclusion, are there significant changes and creative interventions to change the race, class and gender profiles of the producers and shapers of knowledge?

It is hoped that this kind of analysis could serve as a clearing ground for the task of re-imagining the possibilities for and recognizing the limits of producing knowledge for society and revisiting the terms of intellectual engagement in social change in South Africa in an environment made more complex by the demands of the knowledge economy and the reputational economy.

------

>> Téléchargez/Download the working paper

>> Accès au Prix Charles et Monique Morazé 2013

Intervention / Responsable scientifique

Dans la même collection

-

Prix Charles et Monique Morazé 2016

KleicheMinaMoulinAnne-MarieDozonJean-PierreCraveriMartaCréé en 2013 par la FMSH, le prix couronne des travaux de chercheurs confirmés traitant soit de la thématique sciences et société, soit de la problématique éducation et société. Le prix 2016 est

-

Prix Charles et Monique Morazé 2015 : Enseignement supérieur, justice et société

Le Prix Charles et Monique Morazé, remis par la Fondation Maison des sciences de l’homme pour la troisième fois, a été créé pour distinguer des travaux portant sur deux grands thèmes : éducation et

-

Prix Charles et Monique Morazé 2013 - Science Technology and Society

WieviorkaMichelKrishnaV. V.PandeyIndra ManiWaastRolandPaponPierreLe premier lauréat du Prix Charles et Monique Morazé est la revue Science, Technology and Society, lancée à New Delhi en 1996 avec le soutien de la FMSH par une équipe menée par Venni V. Krishna

Avec les mêmes intervenants et intervenantes

-

Introduction et présentation du rapport IPEV 1 - Colloque international Rabat 2019

DozonJean-PierreWieviorkaMichelFerretJérômeThomasDominiqueStrausScottColloque international Violence et sortie de la violence en Afrique méditerranéenne et subsaharienne FMSH – UIR (Chaire CSFR)

-

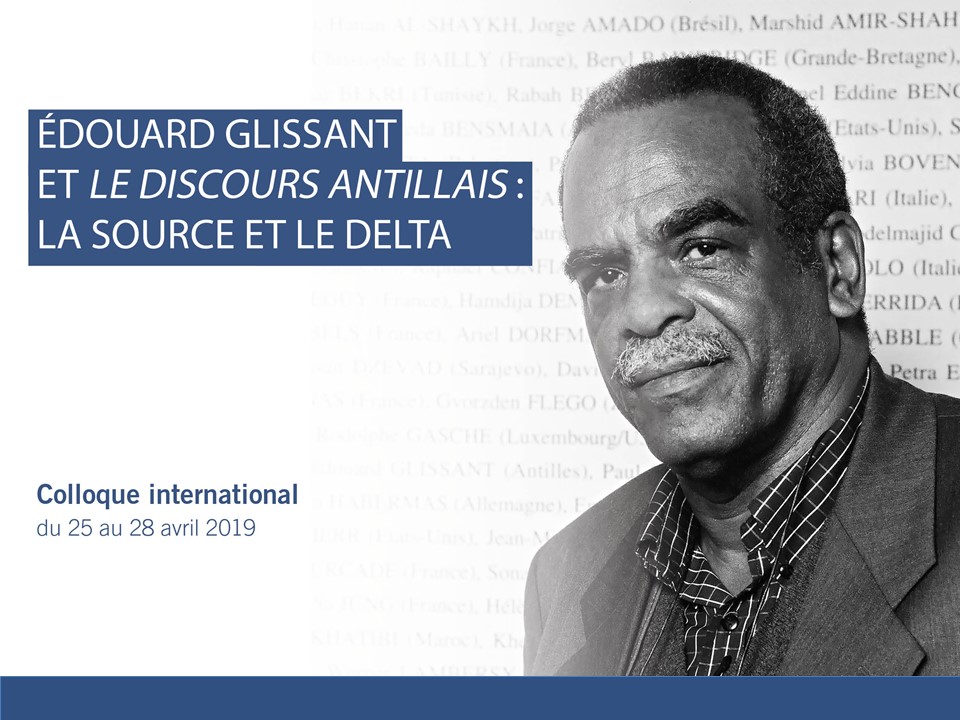

ÉDOUARD GLISSANT ET LE DISCOURS ANTILLAIS : LA SOURCE ET LE DELTA - PARTIE 1

CoursilJacquesCéryLoïcGlissantSylvieBundu MalelaBuataDomiSergeDozonJean-PierreLa FMSH a accueilli les deux premières journées de ce colloque qui s'est déroulé du 25 au 28 avril 2019, en même temps que l'exposition « Le Discours antillais d'Édouard Glissant : traces et paysages

-

Introduction et présentation du Groupe MCTM et de la journée d'étude

ChivallonChristineDozonJean-PierreMémoire en strates - Journée d’études Mondes Caraïbes et Transatlantiques en Mouvement | Mercredi 22 mai - Introduction et présentation du Groupe MCTM et de la journée d'étude

-

VIVRE AVEC LES DIEUX - LA FORCE DE L’ANTHROPOLOGIE VISUELLE

AugéMarcColleynJean-PaulWittersheimÉricDozonJean-PierreBoyer-AraújoVéroniqueRencontre | 16 mai 2019 La force de l’anthropologie visuelle Avec ce livre Vivre avec les dieux, récemment publié, et les cinq films documentaires qu’il contient, le lecteur-spectateur

-

MISE EN PERSPECTIVE D'UNE AVANT GARDE INTELLECTUELLE ET POLITIQUE

FragerDominiqueDozonJean-PierreLe groupe et la revue "Socialisme ou Barbarie" - Mardi 19 février Première séance du séminaire Le groupe et la revue Socialisme ou BarbarieSocialisme ou Barbarie est un groupe révolutionnaire

-

MISE EN PERSPECTIVE D'UNE AVANT GARDE INTELLECTUELLE ET POLITIQUE - Séance n°2

FragerDominiqueDozonJean-PierreLe groupe et la revue "Socialisme ou Barbarie" - Deuxième séance - 6 mars 2019

-

Introduction - Jean-Pierre DOZON

DozonJean-PierreCirculation des chercheurs, migrations contraintes : quel impact sur le développement international des SHS ?

-

Yacouba KONATÉ « Sur la réconciliation en Côte d’Ivoire »

DiawaraManthiaKonatéYacoubaDozonJean-PierreConférence organisée dans le cadre du cycle de conférences internationales « Diversité des expériences et causes communes », organisé par Manthia Diawara et Nicole Lapierre, sous l’égide de New York

-

Les Entretiens du Comptoir - Action humanitaire : mutations et réorientations

ChabrolFannyBizouerneCécileCorbetAliceHoursBernardDozonJean-PierreDe l'action humanitaire à l'aide globale Les guerres, les fondamentalismes religieux, les épidémies et épizooties, les changements climatiques et les famines qui s'en suivent, imposent en ce début de

-

Prix Charles et Monique Morazé 2016

KleicheMinaMoulinAnne-MarieDozonJean-PierreCraveriMartaCréé en 2013 par la FMSH, le prix couronne des travaux de chercheurs confirmés traitant soit de la thématique sciences et société, soit de la problématique éducation et société. Le prix 2016 est

-

(Re) créer le monde - 19 mai - Art et mémoire / Écrire l’histoire : une création oulipienne

WieviorkaAnnetteDozonJean-PierreJeudi 19 mai - Philharmonie, salle de conférence 15H50 Art et mémoire : écrire l’histoire : une création oulipienne par Annette WIEVIORKA

-

(Re) créer le monde - 19 mai - Art et mémoire / Du millénarisme à la recréation du monde dans les i…

Jewsiewicki-KossBogumiłDozonJean-PierreJeudi 19 mai - Philharmonie, salle de conférence 15H50 Art et mémoire : du millénarisme à la recréation du monde dans les imaginaires congolais par Bogumil JEWSIEWICKI

Sur le même thème

-

Les nouvelles sociabilités

MilardBéatriceAssiste-t-on à une perte ou un renouveau des sociabilités dans nos sociétés ? Internet et les dispositifs de mise en relation (notamment les nombreux médias sociaux) ont-ils renforcé la sociabilité

-

Les filles d’Eugénie

Trois rencontres avec un génie

-

Chroniques baka, district de Messok, Est Cameroun, mars 2013 : les pièges à souris

DudaRomainL'acquisition des techniques et des connaissances de chasse chez les Baka commence dès l'enfance.

-

comment les historiens affrontent la violence du 20ème siècle

Comment les historiens affrontent la violence du 20ème siècle Conférence d’Henry Laurens, Professeur d’histoire contemporaine du monde arabe au Collège de France, organisée avec le soutien de l'IEA de

-

Chronique aka, décembre 1993 Zomia, Lobaye RCA : réveils et petits déjeuners des enfants à côté d’u…

EpelboinAlainLes résidents d'Akungu se sont installés pour un temps à Zomia, sur un terrain de surface limitée dépendant de la mission catholique. Le cercle des cases est très reserré et les gens sont beaucoup

-

1993 Epelboin A. Chronique aka, 2 décembre 1993 Akungu, Lobaye RCA : dictature du petit cousin

Le fils de Mangutu est soumis à la dictature de son cousin plus jeune que lui, c'est à dire du fils unique de Mbonga, frère ainé de sa mère. L'enjeu c'est une dangereuse lime métalique avec laquelle

-

Présentation du projet ScouTo

VanhoenackerMaximeDes cohortes de jeunes gens sont passées par le scoutisme et le guidisme en France depuis que cette innovation pédagogique y a vu le jour en 1911, quatre ans après son invention par le britannique

-

Regarder grandir Elsa, de septembre 1988 à avril 1991 en 145 mn

TaiebJean-MarcDe la naissance d'Elsa à celle de sa soeur Héléne, le spectateur suit minutieusement le développement du bébé et les interactions avec sa mère, alors secrétaire médicale, sa soeur aînée adolescente et

-

La parole muette de Yacine

EpelboinAlainACTEURS Yacine la fillette sourde muette, Nyanya sa copine, ses soeurs, sa mère fabricante de balayettes, son père, fabricant de chapelets et des enfants du voisinage Il s'agit du suivi vidéographique

-

Forest camp cooking : a meal of porcupine. Baka chronicles. Messok district, East Cameroon, June 20…

DudaRomainCamera, sound, editing : Romain Duda The brush-tailed porcupine (Atherurus africanus) is one of the most appreciated and hunted game species in Central Africa. Abundant near the villages, this

-

Chronique aka, avril 1987 : travail, jeux et toilettes d'enfants ngbaka au bord de l'Oubangui

EpelboinAlainAccompagnement d'enfants lors de leurs activités au bord de l'eau dans le fleuve Oubangui : toilettes du petit dernier par ses grandes soeurs et tantes, lessive, vaisselle et toilette des fillettes et

-

Baguenaude au Musée de l'Homme : aller à l'école de la diversité

EpelboinAlainDans la série Baguenaude au Musée de l'Homme, nous suivons les réactions de Julienne Ngoundoung Anoko, socio-anthropologue, spécialisée notamment dans l'anthropologie du genre, de la santé publique,