Notice

Jennifer Meier - The influence of the zeitgeist on the development of cultural learning in foreign language teaching in Germany from 1945 to the present.

- document 1 document 2 document 3

- niveau 1 niveau 2 niveau 3

Descriptif

Since the 19th century researchers have been investigatingthe question whether we need to learn about culture in the foreign languageclassroom or not (e.g., Volkmann 2010: 1), and it now seems clear that languageand culture cannot be thought of separately. A glance at German curricula isenough to see that the German classroom today combines foreign languagelearning with intercultural competence (e.g., KMK 2012: 12; ISB 2021) and has nowfurther developed a global perspective. But where does this “cultural insight”come from, and to what extent is it linked to political and social trends? Inother words, how does the zeitgeistinfluence the development of cultural learning within foreign language teaching(e.g., Klippel, Friederike/Ruiz. Dorottya 2020, Schröder 2018; Fend 2016; Volkmann2010).

The question is closely linked to what is understoodby culture, because this question alone changes how we learn about it and, thus,changes the rhythm of foreign language learning. In the last 70 years alone – sincethe collapse of the Third Reich – this approach to what culture is and how it canbe learned has changed immensely, particularly in Germany, but more broadly inEurope and throughout the world. Researchers in the cultural sciences alonehave discussed and put forward new theses. As previously indicated, the conceptof culture has changed enormously in the school landscape in Germany. While a particularlynarrow concept of culture was still used at the beginning of the 1950s and1960s, a semiotic concept of culture is assumed and represented in today’s curricula.Thus, cultural learning evolved from the still-used cultural studies of the ‘20sand ‘30s, to area studies (Landeskunde)and, finally, to intercultural learning. The university sector is alreadyfurther along in this process and speaks of transcultural or global learning ora combination of intercultural and global learning (e.g. Volkmann 2010;Doff/Schulz/Engler: 2011; OECD 2018, Delanoy 2017).

With this discourse, I would like to highlightand deepen the developments of cultural learning in foreign language teaching inGermany, with a special focus on English teaching. This began with the upheavalin foreign language learning after 1945 and continued until around 1970, which representeda tentative beginning of cultural learning and an incorporation of what was consideredappropriate at that time. This was followed by Landeskunde (area studies), which fostered mainly basic knowledgeabout the target culture in order to be able to interact abroad. Landeskunde controlled foreign languageteaching until the 1990s and finally led to intercultural learning, which stilldominates language teaching today. Interwoven with each other are thesocio-political influences (e.g., de Cillia/Klippel 2016: 626) on foreignlanguage teaching and the respective cultural definitions of terms, which have alsocertainly influenced the learning of culture. My thesis is that the spirit ofthe times has influenced the content of foreign language teaching, and thatlearning about culture has become more important today than ever before. Thisis recognisable in the external geopolitical or historical-political influencesof the respective eras. External factors were and are decisive for thedevelopment of the school's content and orientation (Fend: 183). After theSecond World War, a return to democratic and international values began. Thefirst curricula were developed in the 1950s, and the desire for more foreignlanguages grew as a result of the economic upswing and the increasinglyinterconnected world. In the 1960s and 1970s, language teaching research becameincreasingly important. For foreign language teaching, this meant that thefocus was no longer only on functional language use, but on communicative use,which for the first time also included socio-cultural aspects (Hymes 1972,Piepho 1974). In the 1980s/90s the communicative approach led to interculturalcommunicative competence, which combined the socio-cultural with the foreigncultural perspective. Of course, socio- and geo-political influences also playa major role, such as new technologies like the internet, a more networkedworld, mass migration, etc. (Volkmann 2010: 12). Furthermore, the EU has emergedto prominence, which is why an orientation towards a European community beganalready in the 50s. Even if the European Constitution has not been ratified,there is a European motto (‘United in Diversity’) and more importantly, aEuropean curriculum. The Common European Frameworkof Reference (2001) has had an immense effect on language learning inEurope. In Germany it has led to a change of curricula: now there is anorientation towards competences thatare formulated similarly to those in the CEFR. In 2020 a new edition of theCEFR was relaunched. Once more, this will surely have a significant impact on foreignlanguage learning and on the implementation of learning about culture.

Bibliography

Byram, Michael (1997). Teachingand Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Multilingual Matters:Clevedon.

Byram, Michael, Golubeva, Irina, Hui, Han &Wagner, Manuela (eds.) (2017). From Principles to Practice in Education forIntercultural Citizenship. Multilingual Matters.

Councilof Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning,Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume. Council of Europe Publishing,Strasbourg. [www.coe.int/lang-CEFR;last accessed 9.2.2021].

Council of Europe (2016). Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingualand intercultural education. Beacco, Jean-Claude/Byram, Michael/ Cavalli, Marisaet al. (eds.). Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg. [https://www.coe.int/en/web/language-policy/guide-for-the-development-an… accessed 13.02.2021].

Council of Europe (2020). Common EuropeanFramework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching,assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg. [www.coe.int/lang-cefr;last accessed: 13.02.2021].

De Cilia, Rudolf/ Klippel, Friderike (20166). “Geschichte desFremdsprachenunterrichts in deutschsprachigen Lädern seit 1945”. Handbuch Fremdsprachenunterricht. Burwitz-Melzer, Eva / Mehlhorn, Grit / Riemer,Claudia et. al. (eds.) Tübingen: Narr, pp. 625-631.

Delanoy,Werner (2017³). “From Inter to Trans‘? Or: Quo vadis Cultural Learning?“. Basic Issues. Eisenmann, Maria/Summer,Theresa (eds.). Heidelberg: Winter, pp. 157-169.

Doff, Sabine / Schulze-Engler, Frank (eds.) (2011). Beyond ‚Other Cultures‘. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag.

Fend,Helmut (2006). Geschichte des Bildungswesens.Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Hüllen,Werner (2005). Kleine Geschichte des Fremdsprachenlernens.Berlin: Schmidt.

Hymes, D. H (1972). “On Communicative Competence”. Sociolinguistics. J.B. Pride/JanetHolmes (eds.). Harmondsworth:Penguin, pp. 269-293.

Klippel,Friederike (2020). “Nationaler und internationaler Austausch – das Entstehenener breiten Diskrusgemeinschaft zum neusprachlichen Unterricht in derreformzeit.” Zeitschrift fürFremdsprachenforschung 31: 1, pp. 63-82.

Klippel,Friederike/Ruiz. Dorottya (2020). “Umbruchphasen in der Geschichte desFremdsprachenunterrichts: Konstanz und Wandel.” Zeitschrift für Fremdsprachenforschung 31: 1, pp. 3-6.

McLelland,Nicola and Richard Smith (eds.) (2018). The History of Language Learning and Teaching, Vol. III: AcrossCultures. Oxford: Legenda.

OECD. (2018). Preparing our youth for an inclusive andsustainable world: The OECD PISA global competence framework. [https://www.oecd.org/education/Global-competency-for-an-inclusive-world… accessed 09 November 2020].

Piepho, Hans-Eberhard (1974). Kommunikative Kompetenz als übergeordnetesLernziel im Englischunterricht. Dornburg: Frankonius.

Ruisz, Dorottya (2020). Deutsche Englischlehrwerdeum 1945 – Ein echter Neubeginn? Zwei Mittelstufenbücher im Vergleich. Zeitschrift für Fremdsprachenforschung 31: 1,99-122.

Sekretariatder ständigen Konferenz der Länder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (KMK)(2012). Beschlüsse derKultusministerkonferenz Bildungsstandards für die erste Fremdsprache(Englisch/Französisch). [https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2012/2012… accessed 13.02.2021].

Staatsinstitutfür Schulqualität und Bildungsforschung (ISB), München. LehrplanPLUS Realschule. Fachprofil Moderne Fremdsprachen. [https://www.lehrplanplus.bayern.de/fachprofil/realschule/englisch/auspr… accessed 10 February 2021].

Staatsinstitutfür Schulqualität und Bildungsforschung (ISB), München. LehrplanPLUS Gymnasium. Fachprofil Moderne Fremdsprachen. [https://www.lehrplanplus.bayern.de/fachprofil/gymnasium/englisch/auspra…;last accessed 10 February 2021].

Schubel, Friedrich (1966). Methodik desEnglischunterrichts für höhere Schulen. Diesterweg: Frankfurt am Main.

Welsch, Wolfgang(1999). „Transculturality- The Puzzling Form of Cultures Today”. Featherstone,Mike/ Lash, Scott (eds.). Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World. Sage:London, pp. 194-213.

Dans la même collection

-

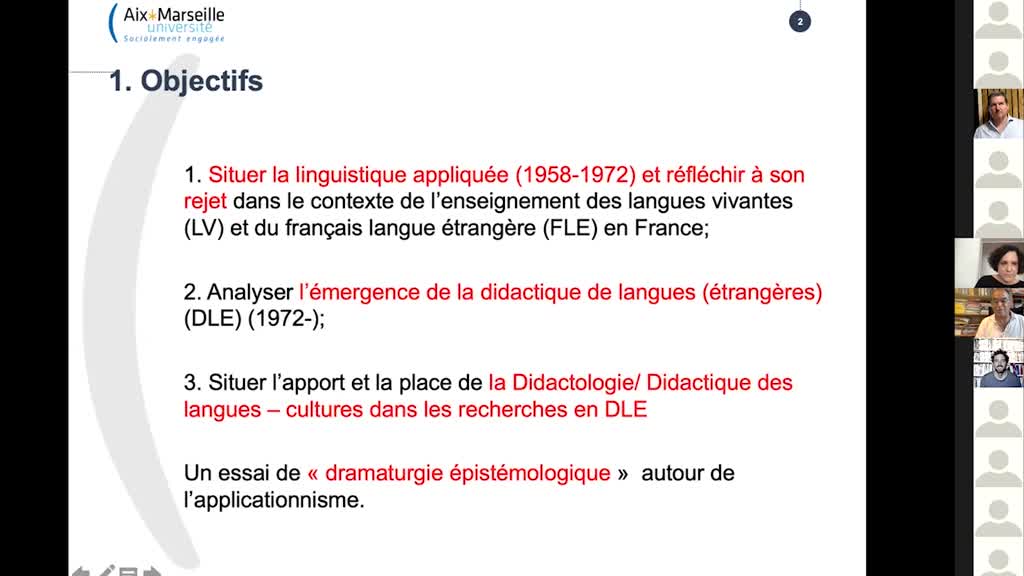

Georges Daniel VERONIQUE - Contre l’applicationnisme linguistique, la Didactologie des langues-cult…

Le terme de linguistique appliquée émerge en Europe à la fin des années 50. En France, le Centre de Linguistique Appliquée de Besançon (CLAB) est créé en 1958. Une décennie de travaux en

-

Alper ASLAN - Le DELF (Diplôme d’études en langue française) : un passé sans histoire ?

Créé en 1985, le DELF représente un enjeu important tant sur le plan politique que sur le plan économique (Coste, 2014). Malgré son rôle dans la diffusion du français, l’histoire du DELF dans le

-

David Bel - Quelle(s) histoire(s) pour la didactique du FLE?

Quand une discipline perd son passé, elle perd aussi son avenir (Galisson, 1988) Cette interpellation forte de Robert Galisson nous amène d’une part à considérer sérieusement l’historicité de

-

Polina Shvanyukova - Language Education and Gender Studies: Focus on Italy, 1975 – 2015

In this contribution I shall explore the link between language teaching and the topical research area of Gender Studies (cf. Sunderland 1994, Pavlenko et al. 2001, Decke-Cornill and Volkmann 2007,

-

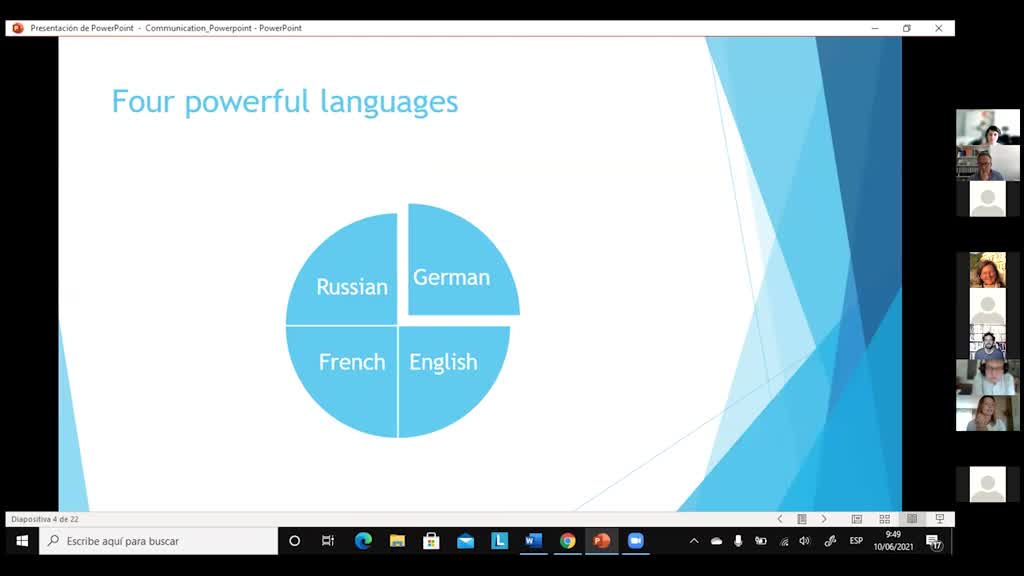

Maxi Pauser - Tertiary Language Teaching and Learning principles: The Case of German L3 at Spanish …

In the last quarter of 20th century the communicative approach or communicative language teaching (CLT) has been gaining importance and popularity at an accelerated rate in all European countries.

-

Javier SUSO LÓPEZ - Approche humaniste vs approche scientifique dans la didactique des langues viva…

Le tournant scientifique dans la didactique des langues vivantes annoncé par H. Palmer (1917, The Scientific Study and Teaching of Languages ; 1926, The Principles of Language Study) se consolide dans

-

John DANIELS - Theories informing French language teaching in an English middle school; an autobio…

This paper draws on the author’s experience as French language teacher and researcher in an English middle school from 1971-2007. Particular attention is given to the ‘revolutionary’ (Stern, 1983),

-

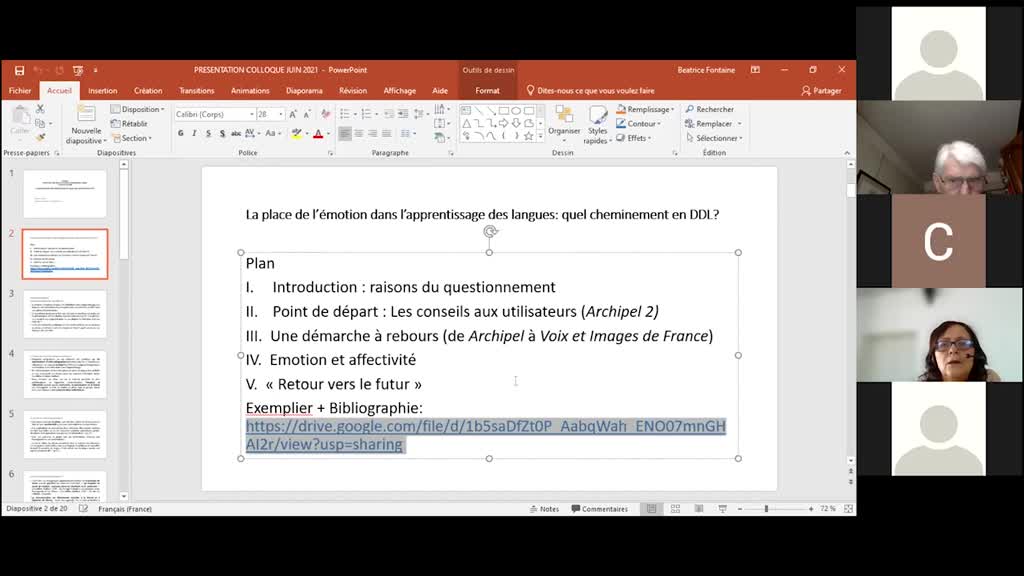

Fontaine Béatrice - La place de l’émotion dans l’apprentissage des langues : quel cheminement en DD…

On s’interrogera, dans la contribution proposée, sur les liens entre la montée en force d’une approche communicative puis actionnelle en didactique des langues et la prise en compte d’aspects

-

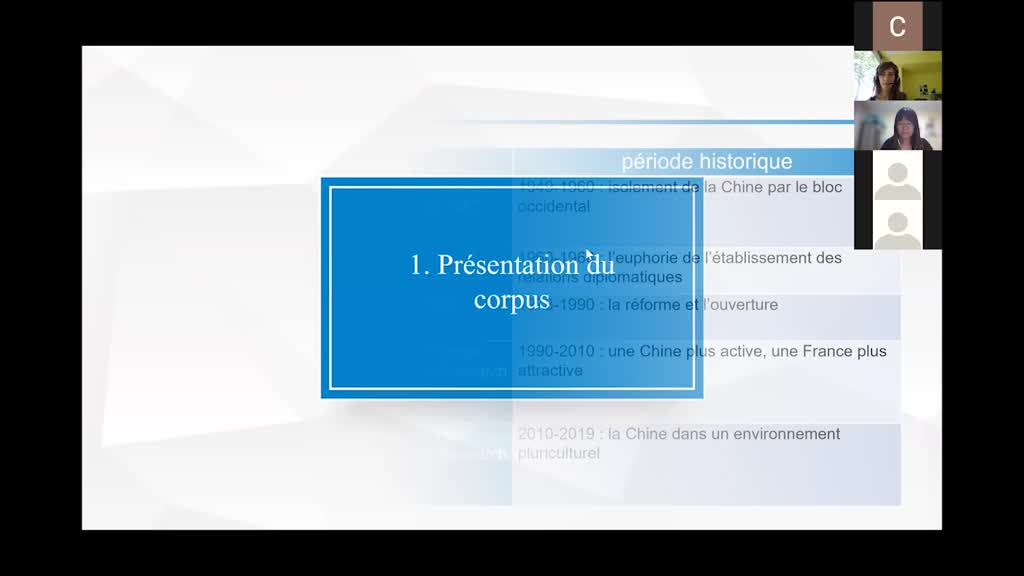

ZHANG Ge - La culture française dans les manuels de FLE en Chine de 1949 à 2019 : représentation…

Parmi les trois pôles fondamentaux qui composent le triangle didactique, à savoir la langue, le sujet et le monde, le premier a été pendant longtemps privilégié. La langue, la culture, la